3 little-known reasons why plastic recycling could actually make things worse

By Pascal Scherrer, Southern Cross University

This week in Paris, negotiators from around the world are convening for a United Nations meeting. They will tackle a thorny problem: finding a globally binding solution for plastic pollution.

Of the staggering 460 million tonnes of plastic used globally in 2019 alone, much is used only once and thrown away. About 40% of plastic waste comes from packaging. Almost two-thirds of plastic waste comes from items with lifetimes of less than five years.

The plastic waste that escapes into nature persists and breaks up into smaller and smaller pieces, eventually becoming microplastics. Plastics now contaminate virtually every environment, from mountain peaks to oceans. Plastic has entered vital systems such as our food chain and even the human blood stream.

Governments and industry increasingly acknowledge the urgent need to reduce plastic pollution. They are introducing rules and incentives to help businesses stop using single-use plastics while also encouraging collection and recycling.

As a sustainability researcher, I explore opportunities to reduce plastic waste in sectors such as tourism, hospitality and meat production. I know how quickly we could make big changes. But I’ve also seen how quick-fix solutions can create complex future problems. So we must proceed with caution.

Plastic avoidance is top priority

We must urgently eliminate waste and build a so-called “circular economy”. For plastics, that means reuse or recycling back into the same type of plastic, not lower grade plastic. The plastic can be used to make similar products that then can be recycled again and again.

This means plastics should only be used where they can be captured at their end of life and recycled into a product of the same or higher value, with as little loss as possible.

Probably the only example of this to date is the recycling of PET (polyethylene terephthalate) soft-drink bottles in Norway and Switzerland. They boast recovery rates of 97% and 95% respectively.

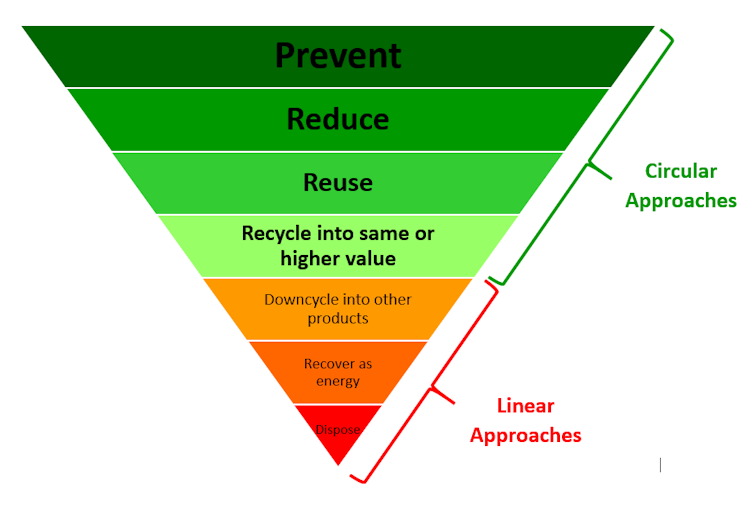

The waste management pyramid below shows how to prioritise actions to lessen the waste problem. It is particularly relevant to single-use plastics. Our top priority, demanding the biggest investment, is prevention and reduction through redesign of products.

Where elimination is not yet achievable, reuse solutions or recycling to the same or higher-level products can be sought to make plastics circular.

In the inverted pyramid of waste management priorities, downcycling is almost the last resort.

In the inverted pyramid of waste management priorities, downcycling is almost the last resort.

Pascal Scherrer

Unfortunately, a lack of high-quality reprocessing facilities means plastic waste keeps growing. In Australia, plastic is largely “downcycled”, which means it is recycled into lower quality plastics.

This can seem like an attractive way to deal with waste-plastic stockpiles, particularly after the recent collapse of soft-plastics recycler RedCycle. But downcycling risks doing more harm than good. Here are three reasons why:

1. Replacing wood with recycled plastics risks contaminating our wildest natural spaces

An increasing number of benches, tables, bollards and boardwalks are being made from recycled plastic. This shift away from timber is touted as a sustainable step – but caution is warranted when introducing these products to pristine areas such as national parks.

Wood is naturally present in those areas. It has a proven record of longevity and, when degrading, does not introduce foreign matter into the natural system.

Swapping wood for plastic may introduce microplastics into the few remaining places relatively free of them. Replacing wood with downcycled plastics also risks plastic pollution through weathering or fire.

2. Taking circular plastics from their closed loop to meet recycled-content targets creates more waste

Clear PET bottles used for beverages are the most circular plastic stream in Australia, approaching a 70% recovery rate. When these bottles are recycled back into clear PET bottles, they are circular plastics.

However, the used PET bottles are increasingly being turned into meat trays, berry punnets and mayonnaise jars to help producers meet the 2025 National Packaging Target of 50% recycled content (on average) in packaging.

The problem is the current industry specifications for plastics recovery allow only downcycling of these trays, punnets and jars. This means that circular PET is removed from a closed loop into a lower-grade recovery stream. This leads to non-circular downcycling and more plastic sent to landfill.

3. Using “compostable” plastics in non-compostable conditions creates still more plastic pollution

Increasingly, plastics are labelled as compostable and biodegradable. However, well-intended use of compostable plastics can cause long-term plastic pollution.

At the right temperature with the right amount of moisture, compostable plastics breakdown into soil. But if the conditions are not “just right”, they won’t break down at all.

For example, when a landscape architect or engineer uses a “compostable” synthetic fabric instead of a natural alternative (such as coir or jute mats) they can inadvertently introduce persistent plastics into the environment. This is because the temperature is not hot enough for the synthetic mat to break down.

We must also differentiate between “home compostable” and “commercially compostable”. Commercial facilities are more effective at composting because they operate under more closely controlled conditions.

Learning from our mistakes

Clearly, we need to reduce our reliance on plastics and shift away from linear systems – including recycling into lower-grade products.

Such downcycling may have a temporary role in dealing with existing plastic in the system while circular recycling capacity is being built. But we must not develop downcycling “solutions” that need a long-term stream of plastic waste to remain viable.

What’s more, downcycling requires constantly finding new markets for their lower-grade products. Circular systems are more robust.

So, to the negotiators in Paris, yes the shift to a circular plastics economy is urgent. But beware of good intentions that could ultimately make things worse.![]()

Pascal Scherrer, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Business, Law and Art, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos