Celebrating Australian Made – GPC Electronics

Our Celebrating Australian Made editorial series continues today with a profile of one company that has seen the rise, and at least partial retreat of globalisation and offshoring – Australia’s largest electronics manufacturer GPC Electronics. By Peter Roberts.

There have been a number of tentative renaissances of Australian manufacturing since protectionism was withdrawn and the sector began its decline in importance, all with the background of a world economy that was discovering low cost countries and the value of making long production runs in places like China.

It was in one of these periods in 1985 that GPC Electronics, now Australia’s largest electronics manufacturer, was founded by Chris Janssen, one of dozens of smart electrical and electronics firms that sprang up to displace traditional manufacturers being left behind by the pace of electronics innovation.

While Chris started GPC at Penrith in western Sydney, manufacturing printed circuit board (PCB) assemblies and telecommunications equipment including eventually the standard Telecom telephone handset – GPC only stopped making those museum pieces three years ago – his brother Peter ran the Utilux wiring and connectors company.

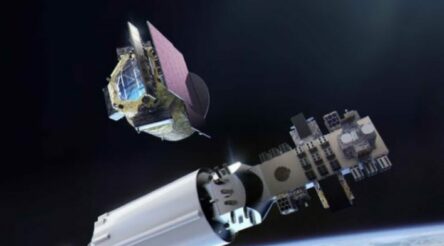

Chris Janssen told @AuManufacturing: “The electronics industry was just starting up and it was at something like the stage where the space sector is today.

“We had a lot of Australian companies starting up in the 1980s making product for what is now Telstra, but customised for Australia. We weren’t making just standard equipment, it was special in some way.”

Janssen – a doctor who switched professions after completing an MBA – manufactured printed circuit board and electronics for the likes of Toshiba, Nortel, Alcatel, with EFTPOS terminals for Ingenico an early opportunity – saw strong growth during the 1990s.

The currency was relatively low, manufacturing in low cost countries was not well established, government policy was supportive, and rapid response to Australia’s smaller, but more varied production demands supported onshore supply chains and proximity to the customer.

In the early 2000’s the arguments for offshoring became more compelling, and with a tripling in the prices for Australia’s mining exports in the decade to 2012 the currency started rising to the unprecedented levels of the mining boom.

The Janssens responded by moving the Utilux business to China and eventually selling it, and by opening a complementary GPC factory in Shenzhen, China which would make longer, standardised production runs, while Penrith – and a later Christchurch plant – commercialised products for customers and made shorter production run products or those that required rapid response.

“Electronics has gone through a number of different phases.

“Electronics are becoming more ubiquitous opportunities and there are many more different fields today – communications, computers, agriculture, defence, power supplies and industrial controls.”

Janssen found that once he had decided to sub-contract manufacture to the world’s largest firms, they preferred their suppliers not to have their own intellectual property IP and branded products. If GPC had ventured to do that, its customers would have been concerned that if supply lines tightened as they have today, that they would naturally divert critical parts to their own products before those of their customers.

“So many companies have been burnt by companies selling excess capacity.

“We are still working here with many global companies, and everything we do is build to print or third party contracting.

“We have very robust manufacturing processes. We know what we are doing and what we do is very reproduceable and our yields are very high.

“W also developed agility – we do high product mix or customisation for customers, and we make small batches, in fact we do products in the hundreds of thousands and we do one offs.”

One customer is the Daikin air conditioning company whose Sydney factory gets its electronics almost as if GPC were an internal supplier – it tells GPC its needs for the following week, and that gets delivered then.

In the 2020s GPC is going through something of a domestic boom as new industries such as defence and space gather pace, defence customers onshore for security reasons, and rising freight costs and logistics delays on imports mean making in low cost locations is less reliable and less attractive.

And of course the recent goal of ‘sovereign Australian capability’ is part of a trend towards onshore manufacturing.

Today GPC Electronics’ Penrith plant employs 150, with a total of 600 across its manufacturing sites – all three employ identical manufacturing software and manufacturing processes, ensuring product manufacture can be readily swapped from one to another.

Typical of today’s customers is Boeing Defence Australia which is sourcing a number of complex components for its LAND 2072 Phase 2B Currawong battlespace communication system from GPC.

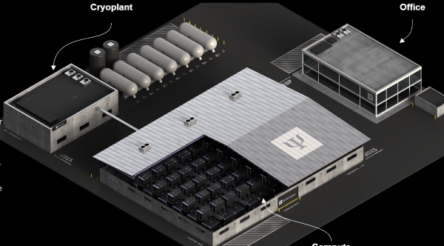

One of those is Boeing’s Tactical Edge Server (TES, pictured below), a high performance computing and network device that will form part of the communication system for Rheinmetall’s LAND 400 Phase 2 BOXER 8×8 Combat Reconnaissance Vehicle being built in Queensland.

Such work requires high levels of manufacturing complexity and automation as well as data security, with the equipment GPC invests in and the capabilities it develops available to work for other customers. Equipment installed at Penrith is generally less than five years old.

Another customer Australian lithium battery manufacturer Energy Renaissance has signed up GPC Electronics as supplier of many of the 32 components of the company’s superStorage battery that it will manufacture at Tomago in NSW.

Energy Renaissance’s local manufacturing push will see 92 per cent of the components of the batteries it will produce made in Australia.

Today globalisation has come somewhat on its head with a deal of onshoring and reshoring going on.

Janssen said the world had probably now passed the high point of globalisation.

“Now freight costs and materials shortages and the inability to travel are affecting (offshore manufacturing).

“People have also seen that doing things locally can create a lot of advantages, a lot of flexibility.

“Today we are seeing more of a pull back from globalisation than a reversal.

“Also in the past couple of years we have seen a lot of manufacturing start ups locally and a lot of innovation, which bodes well for Australian manufacturing in the future.”

Picture: energyrenaissance.com/Chris Janssen at right/Boeing Defence Australia/Tactical Edge Server

![]() @AuManufacturing’s editorial series – Celebrating Australian Made – is brought to you with the support of the Australian Made Campaign Ltd, licensor of the Australian Made logo. For more information about using the logo, visit this link.

@AuManufacturing’s editorial series – Celebrating Australian Made – is brought to you with the support of the Australian Made Campaign Ltd, licensor of the Australian Made logo. For more information about using the logo, visit this link.

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Manufacturing News

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos