Being proactive on SMR possibility

Nuclear power remains banned under two federal laws, but it’s an industry with a lot of industrial potential, believe some Australians. By Brent Balinski.

A small piece of news last week gave a small amount of hope to Australians wanting nuclear energy as part of our future energy mix.

Among 60 recommendations in a NSW Productivity Commission white paper was lifting a ban on nuclear electricity generation for small modular reactors (SMRs.)

These are a new variety of nuclear fission reactors, defined as generating under 300 megawatts per module. Some will tell you that SMRs are not all that new, and have been operating in some form as long as there have been nuclear-powered submarines and ice-breakers.

According to Michael Sharpe, National Director for Industry at the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre and the founder of a new Nuclear Capabilities Forum, they’re an answer to high energy prices faced by Australian companies.

“My plan is for more Australian manufacturers to join the existing global supply chains for the nuclear power industry and build those skills,” says Michael Sharpe.

“For a stronger manufacturing future in Australia we must tackle these big issues,” he tells @AuManufacturing, mentioning pressures at aluminium smelters in Portland and Tomago, and Brickworks’ claim that their products are cheaper to make in the US and then ship here versus make here.

“We have massive reserves of uranium, yet we dig the stuff out of the ground and ship it all over the world for others to benefit.”

ANSTO explains that SMRs have three main differences to traditional nuclear generators, around simplicity in design and installation, being prefabricated and then installed onsite; a higher level of inherent safety; and Emergency Planning Zones — a site's boundary for SMRs versus a 16 kilometre radius needed to satisfy US regulators.

Other claimed benefits include compatibility with current electricity grids, ability to load follow (stepping in for intermittency in renewable generation), and no requirement for a large supply of water.

The International Atomic Energy Agency counts around 50 different designs worldwide.

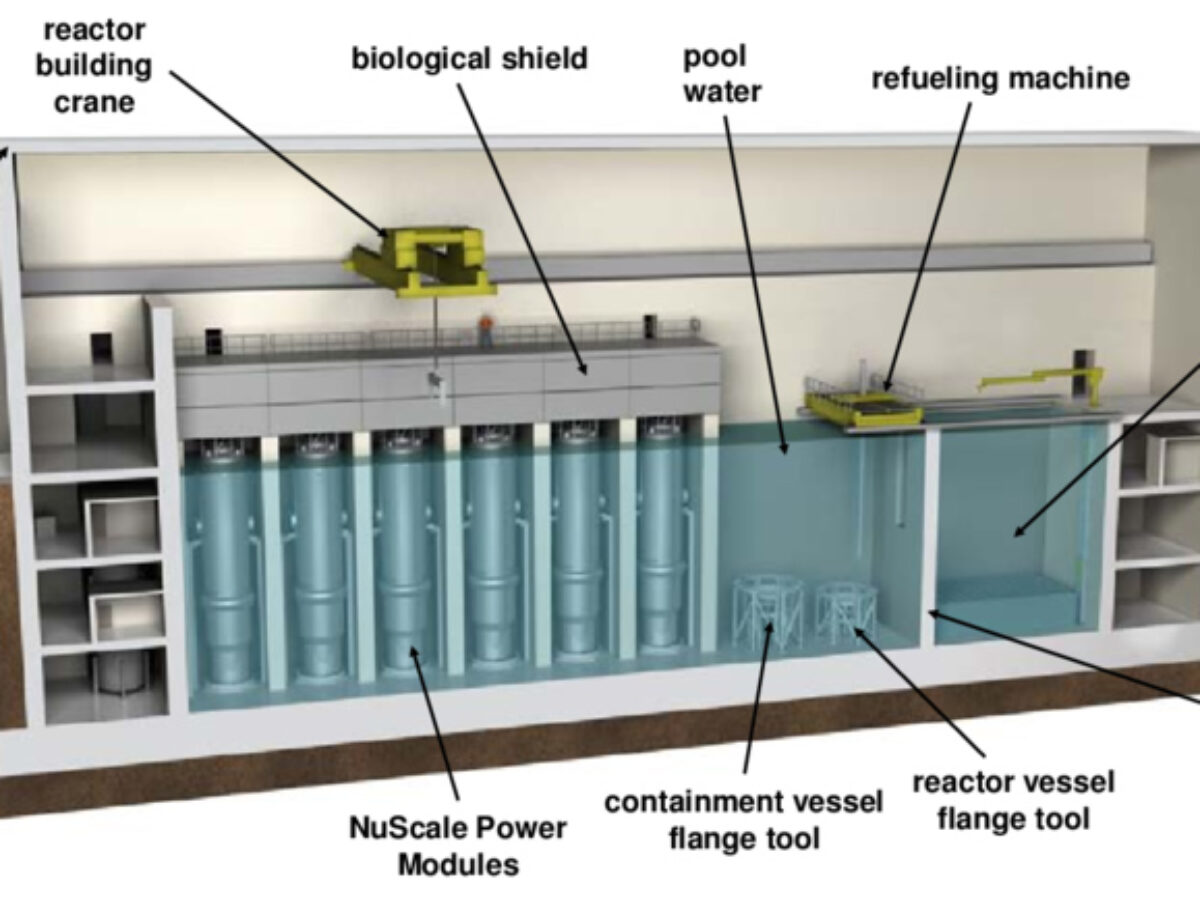

Designers so far include Westinghouse, GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy and NuScale Power.

The latter describes its modules (up to 12 can be stacked together at an installation) as providing 77 megawatts of power, weighing 700 tons, and 65 feet tall with 9 feet diameter.

NuScale received the first design approval from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission last year. Its first commercial operation — 12 modules at Idaho Falls — is scheduled to begin operating in 2026.

“We would be surprised”

Dr Edward Obbard, a nuclear materials engineer and senior lecturer at the University of NSW, sees SMRs as making sense in terms of energy security and goals to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions.

“We can only keep on trying to square the circle and come up with a national energy supply without any primary fuel for so long,” he tells @AuManufacturing.

Obbard’s university runs Australia’s only nuclear engineering education program, and he says Australian R&D capacity is concentrated at one national lab (ANSTO) and a few universities.

He adds that it is an industry sector with a lot of overlap with other technical fields — such as civil, electrical, instrumentation and control. If existing R&D in those fields was directed at specific nuclear applications, “then very soon we would be surprised to find ourselves comparable to other small-ish countries using nuclear energy already, e.g. Sweden, Finland, Spain, Czech republic.”

Another perspective is from David Fox, General Manager at LA Services, who would also like to see a local nuclear industry flourish.

He points out the recommendation last week is limited to electricity generation, and an important sovereign capability aspect seems overlooked.

Nuclear energy is a highly-advanced industry, requiring an ecosystem of top-notch scientific, engineering and manufacturing skills to sustain it.

“If we were able to get past the current polarising electricity generation debate and small modular reactor innovation became an acceptable means of energy for a range of applications, then it would bring a new dimension to the local pressure equipment industry and the smart industrial asset arena,” says Fox, whose company specialises in pressure vessel fabrication.

“If we were able to get past the current polarising electricity generation debate and small modular reactor innovation became an acceptable means of energy for a range of applications, then it would bring a new dimension to the local pressure equipment industry and the smart industrial asset arena,” says Fox, whose company specialises in pressure vessel fabrication.

The discussion needs to be framed in terms of lifting the country’s overall industrial sophistication. Examples are in the ways it feeds into other high-technology sectors, such as defence and space.

“The push for Australia to develop a cutting-edge competitive space industry is evident. So how do our scientists, engineers and investors do that when nuclear thermal propulsion is off the table for regulatory reasons, and yet other advanced nations are developing the capability?” asks Fox.

An export opportunity?

There are plenty of criticisms when it comes to lifting bans on nuclear power.

For every SMR enthusiast, you can probably find another describing it as vapourware. A comment last week from ETU National and NSW Secretary, Allen Hicks, is illustrative: “small modular reactors, a technology that has been ‘just around the corner’ since the 1970’s but still doesn’t exist…”

The economics — pro or con — are impossible to be clear on, given the lack of adoption, and are based on hypotheticals.

Waste disposal is another issue.

And before any reactor is operating in Australia, you should probably add the time between now and laws changing, plus at least seven years.

According to Sydney-based consultancy SMR Nuclear Technology, construction time would be three years, following four years of “community consultation, site selection, feasibility studies, environmental and development approvals and arranging financial facilities.”

Australia has all the basic infrastructure to manufacture and operate SMRs,” believes Edward Obbard

On the other hand, factors such as targets for lowering emissions can only strengthen the argument for nuclear power. The International Energy Agency sees it making a contribution in a zero-emission scenario, with “output rising steadily by 40% to 2030 and doubling by 2050, though its overall share of generation is below 10% in 2050.”

The pro-nuclear segment in Australia sees an opportunity for manufacturers to be involved.

Obbard says capacity generation in the gigawatt range would mean multiple SMR projects going ahead, perhaps consecutively around the nation, “and a community of specialist trades growing up in that.

“Repetition is the whole point [of] SMR economics. Once you can do it locally then immediately you have an export opportunity as well. Australia has all the basic infrastructure to manufacture and operate SMRs.”

Sharpe believes there’s no point waiting around. He says his group is planning its second meeting, with NuScale’s head of production to join by Zoom.

“My plan is for more Australian manufacturers to join the existing global supply chains for the nuclear power industry and build those skills,” he explains.

“We can grow business opportunities globally with manufacturing of reactors and other parts as required. We will build local jobs here and we’re stepping up to export now. We are ready for a future that includes nuclear power in Australia, today.”

Featured picture: NuScale

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Analysis and Commentary

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos