Can the internet really challenge the age of steam?

By Peter Roberts

Even today, centuries after the invention of the steam engine, there is nothing quite like a powerful railway locomotive with a full head of steam to thrill young and old alike as it converts fuel into raw, muscular, noisy power.

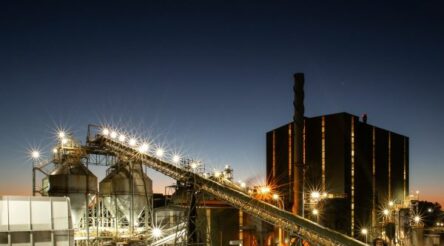

Riding South Australian Railway (SAR) locomotive 621, the Duke of Edinburgh, to the Port of Goolwa (pictured) near the mouth of the River Murray yesterday, bystanders were at every station platform, hillside vantage point and railway crossing, in awe, mobile phones in hand to capture its passing.

Built at Adelaide’s Islington Railway Workshops nearly a century ago, the locomotive is a survivor of an invention that Northwestern University economist Bob Gordon famously once argued argued had a greater impact in productivity terms compared to the internet.

From Goolwa, Australia’s first public railway running on steel rails travelled the short distance across the sand dunes in 1854, opening the Murray river trade to the ocean at Port Elliott, with steam power ultimately accelerating Australia’s economic development and changing the country forever.

By comparison to the age of steam, those mobile phones held by those watching the Duke, capturing images that were no doubt shared a cross the internet, may one day pale into comparative insignificance.

Roy Green, Emeritus Professor at the University of Technology, Sydney and Chair, Port of Newcastle and the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Hub, is one that believes that nothing in the modern age compares with the impact of the steam engine over 200 years ago.

Green said: “It was called the industrial revolution for good reason because it transformed economies and societies throughout the world.”

In fact if you think about the internet age, one of its glaring features in developed societies is its association with a period of anaemic productivity growth.

For Green, a member of @AuManufacturing’s editorial advisory board, there are two lessons in comparing the age of steam to the modern age of the internet.

“The first is that massive wealth can be produced through technological change and innovation, albeit not always distributed fairly.

“The second is that technological pre-eminence in one century may not necessarily be replicated in the next, especially if distribution issues are not resolved.

“Indeed as the speed of change has accelerated, the competitive advantage of nations and firms may be measured in decades…and even measured in months for the latter, rather than centuries.”

It is safe to say that 100 years from now the Duke of Edinburgh will still be drawing excited crowds, but mobile communications and the internet will just be unseen and unheralded background technologies of modern life.

Pictures: Peter Roberts/SAR locomotive 621 at Goolwa railway station

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos