Celebrating Australian Made – a resurgence in industry-building policy by Phillip Toner

@AuManufacturing continues our editorial series – Celebrating Australian Made – with a look at industry policy. Here Phillip Toner of the University of Sydney examines the legacy of the policies which have created today’s hollowed out industrial structure.

During the past four decades the economies of advanced and developing nations have been radically transformed by the adoption of neoliberal ‘market-driven’ policies of deregulating financial and capital markets, globalisation and reducing the role of government in industry development.

However, the major international economic policy institutions such as the OECD, IMF and World Bank, that formerly propagated these market driven policies are now saying these very policies have caused fundamental economic and social problems in advanced economies that are undermining economic growth This is even undermining democracy itself and leading many in the electorates of Europe the US and even Australia to question the legitimacy of capitalism in its current form.

In response these international institutions and national governments, such as the US, are now advocating that ‘the time is over when industrial policies were considered words not to be spoken in decent circles’. Such policies are back in fashion to support economic transformation and capabilities’ development’ (OECD 2015, Industrial Policy: Not a bad word.

Other factors that have led to a serious re-appraisal of policy include the obvious and startling success of Chinese industry policy as the foundation for Chinese business dominating world trade in not only basic commodity production but increasingly high-end technology, such as ICT, motor vehicles, telecommunications, renewable energy equipment and materials science.

The wining combination of coherent and well-resourced industrial development strategies, as stated for example in its Five-Year Plans, harnessed to the profit motive of private enterprise is evident in rapid domestic and export growth.

Closure of international borders for people, goods and services due to COVID has also dramatically reinforced the lack of ‘sovereign’ production capability for many strategic goods and services in many nations.

Finally, there is the now widely acknowledged necessity to de-carbonise economies, a task so monumental that, by itself, will arguably require a level of industry policy intervention unprecedented in peacetime.

The most obvious manifestation of fundamental problems with modern economies is the rise of populism in the US and Europe as wide sections of the electorate are viewing themselves as victims of globalisation and are fed -up with diminished wages and job opportunities for themselves and their children.

Governments are now advocating industry policies, especially focussed on manufacturing and associated services, as a key solution to some of these problems.

Most advanced nations have experienced a ‘hollowing out of the occupational structure’ or a polarisation of occupational growth with an increase in the share of both high and low skill jobs but a fall in the share of middle skill jobs (OECD 2016: 10 Future of Work and Skills Paper presented at the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group).

The loss of middle skills jobs has occurred especially in manufacturing and routine services such as middle management, clerical and data processing. The loss of these jobs is due to a combination of vertical disintegration of production which has seen products and services ‘unbundled’ into discrete components and shifted to a few low-cost global scale production centres.

This has been facilitated by the digitisation of manufacturing and service activities and falling communication and transport costs. Improved productivity in certain sectors has, due to automation and technical change, also seen labour-output ratios decline. There has also been a general increase in import penetration.

The combination of deindustrialisation and the substitution of middle-skill, middle-wage jobs for low productivity, low pay, precarious jobs in industries such as retail, aged care, cafes, accommodation, cleaning and road transport has not only increased income and wealth inequality but also regional growth disparities.

The self-reinforcing effect of such inequality also influences the industrial structure to the extent that disadvantaged groups are much less likely to participate in higher education or obtain training qualifications and this precludes such groups from participating in higher skilled jobs. Conversely, it creates an ever larger labour pool feeding the low pay, low skill, low productivity industries described above.

Dr Phillip Toner is a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Political Economy at the University of Sydney and Adjunct Professor at UTS Business School. He has worked in labour market and economic research for the federal government including an agency of Federal Treasury.

@AuManufacturing’s editorial series – Celebrating Australian Made – leading up to Australian Made Week (24 to 30 May) – is brought to you with the support of the Australian Made Campaign Ltd, licensor of the Australian Made logo.

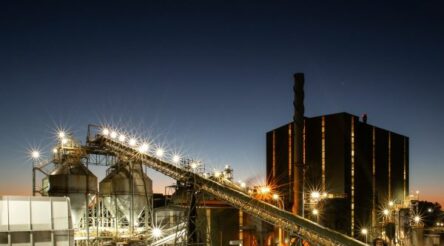

Image: Phillip Toner

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos