Election 22 the real issues – the industry policy dog that didn’t bark by Roy Green

@AuManufacturing’s occasional editorial series on the real issues in the 2022 federal election concludes today with a return to industry and innovation policy – largely missing in action in the election campaign. By Professor Roy Green.

When it comes to research and innovation, the current election campaign recalls the Sherlock Holmes story featuring the dog that didn’t bark.

Here’s how it went – Gregory (Scotland Yard detective): Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?

Holmes: To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.

Gregory: The dog did nothing in the night-time.

Holmes: That was the curious incident.

The problem with assessing the policies of the major parties in this critically important area for the future of our economy and society up to now is that there has been little if anything to assess. But the broad brushstrokes have become more evident in recent days.

The Coalition asks us to endorse their current approach, while Labor has announced a range of new initiatives, primarily focused on the revival and reinvention of Australia’s diminished manufacturing capability.

The question remains whether anything contemplated in this campaign is adequate to address the challenges of sluggish productivity, wage stagnation and energy transition, let alone the transformation of our outdated industrial structure.

Outdated trade and industrial structure

Let’s reflect for a moment on where we are.

Unlike the Norwegians with a 76 per cent resource rent tax and the world’s biggest sovereign wealth fund to underwrite the future diversification of their economy, we failed to take advantage of our commodity boom.

The revenues left over from rich pickings by foreign shareholders fuelled short-term consumption, not the much needed longer term investment in the industries and technologies of the future.

Manufacturing as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from around 30 per cent in the 1960s and 70s to 12 per cent in 2000 after the Hawke-Keating tariff reforms, but showed signs of rebounding in the transition from large scale vertically integrated mass production to smaller, more specialised firms making their way in global markets and value chains.

This repositioning of the Australian economy was interrupted not just by the global financial crisis but more significantly by the commodity price spike that increased our income from the rest of the world, mainly China, but masked a structural deterioration in productivity performance as the high dollar made much of our trade exposed manufacturing uncompetitive.

This experience was also shared by the Netherlands with the discovery of North Sea gas in the 1960s, hence the ‘Dutch disease’, and by the UK with North Sea oil in the 1980s.

As the trade deficit in elaborated transformed manufactures (ETMs) doubled in Australia to $180 billion, the manufacturing share of GDP fell further to six per cent, making us one of the least self-sufficient economies in the OECD. (Though the international data must always be qualified to take account of related services that are not included in the measurement of ‘manufacturing’.)

The narrowing of Australia’s trade and industrial structure is reflected both in our precipitous decline in global competitiveness rankings, and in the Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity which measures the diversity and research intensity of our exports.

Here we have dropped from a ranking of 55 in the 1990s, which was disturbing enough, to 86 out of 133 countries.

Australia’s vulnerability to external shocks was highlighted in the Covid-19 pandemic, when the lack of what we now call ‘sovereign capability’ in essential products became a matter of public policy concern.

And yet once again, domestic consumption was safeguarded, this time by an unprecedented fiscal stimulus, defying previous shibboleths about the dangers of debt and deficits.

And once again, the need for productivity-enhancing investment in technological change and innovation was overlooked, against the background of another volatile commodity price spike.

This was despite the contribution such investment would make to more sustainable, net zero emissions growth, hence reducing our debt in the longer term.

Instead, as a result of this policy neglect, combined business and government expenditure on R&D as a proportion of GDP has slumped to 1.79 per cent, compared with 2.2 per cent eight years ago and 2.4 per cent on average for the OECD.

Some countries such as Israel, Finland, Korea and Switzerland are increasing their R&D spend to four and even five per cent of GDP.

Paradoxically, given the rundown of public funding for higher education, universities have taken on the heavy lifting in research and innovation, mainly through access to increasing international student revenues.

The problem here is not only that these revenues have taken a hit from Covid-19, but the research is not always in the areas where it can have most beneficial impact.

And while there are exemplars, nor is it translated as effectively as it could be into economic and social value.

When the latest Intergenerational Report projects annual productivity growth of 1.5 per cent for the next 20 years as a necessary minimum to maintain living standards, we must look to the policy levers that will assist in achieving that target, from current levels of around 0.5 per cent.

These levers must be designed to build our capability and performance in science, technology and innovation, and to increase enterprise ‘absorptive capacity’.

And yet not only are these levers missing or inadequate in Australia, they scarcely feature in public debate.

National research and innovation system

Most successful advanced countries are committed to the concept of a national research and innovation system, especially as part of post-Covid recovery and reconstruction.

They see this approach as essential to the development of a competitive and dynamic knowledge based economy.

In Australia we are faced not only with market failure in the research and innovation context but with ‘system failure’.

As well as being underfunded, Australia’s approach is notably fragmented and undirected.

In 2015, a Senate report on innovation found that Commonwealth spending is spread over 13 portfolios and 150 budget line items, few of which connected with each other.

Successive governments, including the current one, have become adept at ‘slicing and dicing’ an inadequate budget envelope to create myriad programmes lacking interdependence and critical mass.

Our research and innovation effort is also undirected in the sense that it lacks a coordinating focus with national missions and priorities driven by regular evidence-based ‘foresight’ exercises.

Instead, the largest component of funding is the R&D Tax Incentive programme, whose guidelines have become more opaque as demand continues to grow to the point where its claim on resources is unsustainable.

Other countries make more use of direct targeted programmes aligned to their priorities.

How much of this will change over the next three years?

The Coalition will continue business as usual with a mix of programmes, most of them welcome to recipients but sub-scale and lacking the institutional structures that would ensure longevity of engagement and impact.

Labor has committed to ‘repurpose’ existing programmes and introduce a new $15 billion manufacturing future fund, from which will be drawn grant, loan and equity support initiatives.

Ideally, in addition to further layers of program funding, the next federal Government will need to look hard at the institutional arrangements that deliver this funding and commit to devising a more coherent, cost-effective research and innovation system.

This will require a number of components, the first being a national coordinating agency, similar to those successfully operating elsewhere, such as Sweden’s Vinnova, the Netherlands TNO and InnovateUK.

In this context, the second component of reform is a unified mission-driven approach to support for public research, including basic ‘blue sky’ research, across all discipline areas with independent assessment of grant applications.

It has become dysfunctional and indeed inappropriate for universities to have to backfill research projects with teaching revenues.

Third, while everyone favours increased industry-university collaboration, Australia lacks the structures to conduct this effectively at scale and over long periods of time.

Successful examples around the world, such as the UK Catapult Centres and ManufacturingUSA Institutes, are ‘aggregators’ which bring together the full range of stakeholders in specialised areas, including universities, multinational companies, SME supply chains and CSIRO equivalents.

Fourth, it has also become evident from local as well as international examples how important ‘place-making’ is for the development of innovation and entrepreneurship precincts.

Many of these will be nurtured and grown by individual States, but there is scope for the Commonwealth to provide logistic support and access to finance on a cooperative basis, especially in Australia’s regions.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a world competitive research and innovation system will only be as successful as the skills that are brought to bear in the development and deployment of new technologies, design thinking and innovative business models.

Again this is a question not just of resources but institutional structures for capability building, including closer integration of university and VET pathways.

Australia’s future will not be determined by any single programme or initiative but by a system-wide, research driven transformation of our narrow and unsustainable industrial structure.

While some good ideas have managed to surface over the past week or two, the next government will have to do a lot better than the minimal offering in this election campaign.

The dog still has time to bark.

Roy Green is Emeritus Professor and Special Innovation Advisor at the University of Technology Sydney, Chair of the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Hub and Chair of the Port of Newcastle.

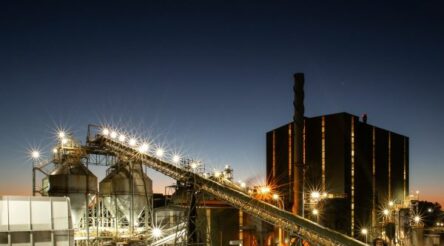

Picture: UTS/Roy Green

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos