Excellence in maritime manufacturing – touring Osborne naval shipyard

Kicking off @AuManufacturing’s editorial series Excellence in maritime manufacturing we visit the Osborne shipyard in Adelaide where nine Hunter class frigates are under construction. Covid-19 and defence concerns have kept journalists away from the shipyard, but here, Peter Roberts reports on an exclusive first-tour.

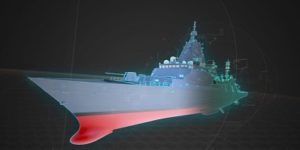

A tour of Australia’s biggest investment in naval shipbuilding facilities begins not in the real world, but in a digital world where the design for our next-generation anti-submarine frigates is taking shape.

More than two million digital artefacts and 90,000 documents – the basis for the design of Australia’s Hunter class frigates – are being transferred from the UK’s Type 26 frigate program in Scotland to Adelaide’s Osborne Naval Shipyard.

BAE Systems Maritime Australia is building the ships on a design derived from on the Global Combat Ship (GCS) baseline design and the Type 26 reference ship currently under construction in Glasgow for the UK’s Royal Navy.

Teams of engineers in Adelaide and Melbourne are utilising technology including a state-of-the-art 4m-wide x 2.5m-high LED wall (pictured, below) that provides a full 2D and 3D view of the Hunter class frigate and is updated continuously from the reference ship design.

This ‘vis suite’ tool is integrating Australia’s preferred Aegis combat management system with the Saab Australia developed Australian Interface, and the CEAFAR2 phased array radar into the design and is updated every 24 hours.

The shipyard, built for BAE Systems by the government owned Australian Naval Infrastructure, is conceived as a fully digital shipyard, the reality now stretching along the banks of the Port River in Adelaide.

Close to the city’s Outer Harbour container terminal and a dolphin sanctuary – and its huge size visible for tens of kilometres across the flat northern Adelaide plains – sits Osborne Naval Shipyard.

Inside the very real yard there are a still a few physical drawings to be found as workers are brought on board and trained, and the manufacturing process is brought up to speed. But generally instructions are passed electronically from the virtual to real world work stations and what will ultimately total 2,500 individual workers.

Proudly showing off steel fabrication and unit assembly building 20, Mick Noi waved expansively as workers marked and cut steel and said: “This is all off a CAD file – we don’t get very many drawings here.”

The first thing you can touch and feel to note is the Hunter frigates are being fabricated and assembled entirely indoors in a complex of massive buildings – hugely white in the sunshine with giant brown painted doors. (main picture).

The most recent warships built on the site – two offshore patrol vessels and three air warfare destroyers – were built out in the open – come rain, hail or shine – so working under cover offers immediate productivity and quality improvements as well as a more comfortable working environment.

Much of the basic fabrication of the ship takes place inside building 20 – a vast group of three conjoined buildings where steel is cut, welded and assembled into large sections.

Part of the process involves robotic welding (below) – robots currently carry our 70 per cent of the welds.

Another system promising improved productivity and quality is a MicroSteps MSLoop shuttle table system (pictured, below) that allows simultaneous loading, processing and unloading of large format plates in a flow manufacturing process.

Large shuttle tables move steel in a continuous loop from one zone to the next, from the loading zone to cutting, weld edge preparation, sandblasting and to the unloading zone. After unloading, the supporting shuttle table then moves under the cutting system back to the starting point.

Once at full shipbuilding speed, the shuttle tabled will ‘pulse’ between the various work stations ten times a day, meaning they have the capacity to aromatically process 15,000 tonnes of steel a year.

Steel is currently being cut to an accuracy of greater than one millimetre, with the resulting welded components coming together into three dimensional ship units at an unprecedented accuracy.

This is reducing the need for rewelding and cutting as the various steel sections are then welded together to form ship units (at rear, below).

Noi said: “The whole idea of this building is to be as accurate as possible to ensure that further down the production process they have to do as little rework as possible.”

Each ship will be made up of 22 ship blocks, and each ship block is made up of four unit modules weighing between 45 and 270 tonnes.

Wheeled carriers then take the modules to building 18 – the blast and paint chamber – and then onto the block consolidation hall.

In the block consolidation hall – building 21 – at Osborne the first prototype block is now being welded together (picture, below).

Ship units are brought into the hall upside down, with further sections – also upside down – lifted and placed on top and welded together. The upside down orientation makes fitting of racks and hangers, pipework, ducts and so on on interior compartments’ ceilings an easier operation – work is carried out at a worker’s feet, rather than them having to reach overhead.

Once welded together and with fittings attached, the ship blocks are transported to the adjoining main assembly hall, (pictured below).

Currently empty save for some stored components the hall is truly massive – more than 187 metres long, 80 metres wide and 50 metres high.

The inside is as long as the playing field at Adelaide Oval, but somehow with little inside to provide scale, it looks deceptively small. Then again, it takes minutes to walk from one end to the other.

Future ship line manager Mitchell Parker said: “It is a beast of a building.

“Later this year in Q4, we will see the first block in here.”

The future HMAS Hunter will soon be assembled from its modules and blocks and strategic equipment added on one side of the hall – ultimately two of the giant vessels will sit side by side in various stages of completion.

The ship’s mast and its Australian developed CEAFAR2 Phased-Array Radar is too tall to be assembled inside even this huge building, with the Hunter to then be wheeled out of one of the giant entrance doors (brown colour in the picture) to the hardstand outside where the mast will be fitted.

Finally, the future HMAS Hunter will be launched for final fit out and testing leading to sea trials, and ultimately service in the Royal Australian Navy.

@AuManufacturing’s editorial series Excellence in maritime manufacturing is brought to you with the support of BAE Systems Australia.

![]()

Picture: Australian Naval Infrastructure/BAE Systems Maritime Australia/MicroStep.com/Aurecon

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Defence

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos