How ‘flags of convenience’ have shrunk Australia’s merchant fleet

By Maritime Logistics Expert, Centre for Supply Chain and Logistics (CSCL), Deakin University

In movies about ships, a crew feverishly changing their vessel’s name and flag to avoid detection is a common tactic. Nothing so simple could work in reality, right?

In a sense, though, running up a different flag is still as useful a corporate tactic as it was to Captain Jack Aubrey disguising the HMS Surprise to defeat the Acheron.

Changing flags largely explains the disappearance of Australian merchant ships. Three decades ago the national merchant fleet numbered about 100. Now it’s just 14.

That’s despite being an island continent where 99% of imports and exports are transported by sea, with thousands of large commercial ships operating in Australian waters.

The decline has many people bothered. The Australian Labor Party is promising to create a “strategic fleet” of up to a dozen ships – oil tankers, gas carriers and container ships – that can be relied on to deliver essential fuel supplies. The ships will be privately owned but could be requisitioned by the government in times of national need.

“It is a national disgrace that an island nation like Australia only has 14 flagged vessels, and it’s in our national interest to fix this,” said the Opposition leader, Bill Shorten.

But the prime minister, Scott Morrison, has dismissed the plan as simply an attempt to protect union jobs.

So who’s right? Does having an Australian merchant fleet matter?

Flying foreign flags

To appreciate what this issue is about, let’s recap what it means to be an “Australian” ship. It’s not necessarily about being Australian-owned.

Mostly it’s about flags.

The flag under which a ship sails determines the conditions the ship and its crew operate.

Australian-flagged ships must abide by Australian laws regarding employment conditions, safety, taxation and environmental regulation. A foreign-flagged ship operates under the rules of the country where it is registered.

About 40% the world’s commercial ships (by tonnage) are registered in just three countries: Panama, Liberia and Marshall Islands. These and other so-called Flags of Convenience countries attract registrations by foreign ship owners looking to avoid the costs of more stringent regulations and tax regimes in their home countries.

Ships registered under flags of convenience are more likely to have unscrupulous owners with crews working under unsafe, exploitative conditions.

Over the past 20-30 years, many Australian companies have made the decision to phase out Australian flagged and crewed ships and replace them with those owned by foreign companies and run by foreign crews, resulting in a dramatic decline in the fleet.

Costs and benefits

In January BHP and BlueScope Steel announced the end of their last two locally operated bulk carriers transporting iron ore from Port Hedland in northwest Western Australia to Port Kembla. The ships, MV Mariloula and MV Lowlands Brilliance, were not Australian-flagged (the former is registered in the Marshall Islands, the latter in Singapore), but were operated by an Australian company (Teekay Australia) employing almost 70 Australian crew.

Technically there are rules to impose Australian standards on all ships operating in Australian waters. Only Australian-flagged (and crewed) ships are able to gain a general licence to operate between Australian ports. But over the years laws granting “temporary” licences to foreign ships have been relaxed.

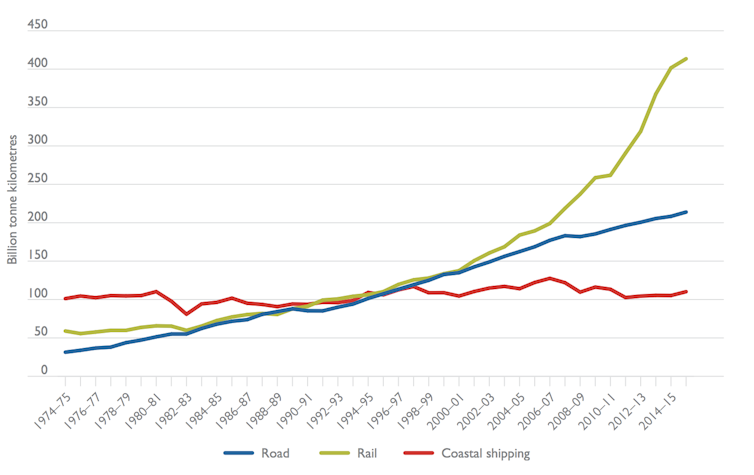

The rationale for allowing them is that their lower costs help local companies stay competitive in global markets. Most inquiries held into Australian shipping have been scathing of the industry’s inefficiencies and high cost. It’s one of the reasons shipping’s share of domestic freight has been falling.

But there are big potential negatives in replacing Australian-flagged ships with foreign-flagged ones.

If we allow foreign-flagged ships in our waters there needs to be adequate oversight by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority) to ensure ships do not pose a greater threat to our precious maritime environment. This is a distinct possibility if crews are not well-trained or do not have proper working conditions.

A stark illustration of such risks was the grounding of the Chinese coal carrier Shen Neng I in 2010. It ran aground on a shoal of the Great Barrier Reef just north of the port of Gladstone, spilling oil and damaging more than 40 hectares of marine park over 10 days. The damage has yet to be repaired.

A government investigation found the ship’s chief mate had only two-and-a-half hours’ sleep in the 38 hours before the accident and made a succession of errors.

Need for bipartisanship

History has shown the importance of a merchant navy in times of conflict or natural disasters. So the Labor Party has a point in arguing government should do more to ensure local shipping remains a viable alternative to road and rail transport.

But it remains to be seen how Labor, should it win the federal election, will counter the trend of several decades and revive the fortunes of Australian shipping. Right now its policy is light on detail, with its only commitment being to establish a “task force”.

Shipping and associated infrastructure require a long investment horizon, so a bipartisan approach to shipping policy is essential. Shipping lines, ship owners, port authorities and unions will all need to cooperate.

Right now that looks optimistic. But other developed nations with high labour costs, such as Britain, the Netherlands, Norway and Denmark, have faced similar problems to Australia and overcome them.

So let’s not wave the white flag quite yet.

This article originally appeared at The Conversation.

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Manufacturing News

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos