Key trade rules will become unenforceable from midnight. Australia should be worried

By Lisa Toohey, Professor of Law, University of Newcastle and Markus Wagner, Associate Professor of Law, University of Wollongong

An important part of the World Trade Organization will cease to function from midnight. December 10 is when the terms of two of the remaining three members of its Appellate Body expire. It is meant to have seven.

The Appellate Body hears appeals from WTO adjudications. If it can’t function, and if there is an appeal, those adjudications have no force. Appointments to the Appellate Body can be blocked by any one of the WTO’s 164 members.

The United States has blocked every proposed appointment and reappointment since June 2017, meaning after midnight the Appellate Body will be left with just one member.

It will be unable to hear new appeals, as the minimum requirement for any decision is three.

Members of the World Trade Organization will still be able to launch complaints and receive initial rulings about trade disputes from December 11, but if any party appeals there will be no means of hearing it and the case might end up in limbo with no resolution.

Did Trump kill the WTO?

While there is much that can be said about the current US President’s attitude towards trade rules, the seeds of the problem predate Trump.

The US began blocking some appointments under the Obama Administration, although Obama was still supportive of the WTO and engaged with it about the future of its Appellate Body. Trump has not engaged with it. He has simply refused to appoint replacements for members who have retired.

There are over 60 different agreements under the WTO umbrella – about 550 pages worth of rules – that operate on a daily basis to smooth worldwide trade.

It is also worth bearing in mind many disputes are headed off at the political level through discussions in WTO committees.

These will remain in place after the Appellate Body ceases to function. By and large, WTO members have adhered to rulings without appealing.

Does it matter for Australia?

Australia needs the WTO dispute settlement system to get justice when political solutions have not been successful. It’s the international equivalent of needing to take your business partner to court when you have tried everything to negotiate a solution.

The WTO dispute settlement system is vitally important for a country such as Australia, which relies heavily on exports for its economic well-being.

In the increasingly uncertain trade environment, Australia has been resorting to it more. Right now, Australia has two big disputes pending.

One is a claim against India’s sugar subsidies. Sugar accounts for the employment of 40,000 Australians. Indian production and export subsidies are driving down international prices at a time when drought and flood are placing immense stress on farmers.

The other dispute is against Canada, where some provinces have restrictions on alcohol sales that make it hard for smaller, foreign producers to get their wine onto shelves. Australian wine exports to Canada have fallen by almost half between 2007 and 2016.

Imagine a world without it

If the attacks on the World Trade Organization continue to the point that the entire organisation collapses, we stand to lose greatly.

Trade would risk returning to the power-based system of settling disputes that preceded the World Trade Organization.

Powerful nations could act as they please, leaving less powerful nations with only diplomatic channels to make their voice heard and little clout.

One-on-one and regional trade agreements would proliferate in the WTO’s place, but they are more complex for businesses to understand and use.

They are also subject to power politics. This is an important consideration for a country like Australia, which relies so heavily on trade with large, powerful partners.

The World Trade Organization is in need of reform. A world without functioning global trade rules will marginalise everyone but the most powerful.

The WTO is down but far from out. It is in Australia’s interest to use what influence it has to restore it.![]()

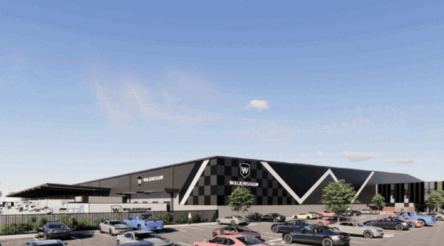

Picture: The World Trade Organization will be defanged but not dead. It’s in Australia’s interest to keep it alive.

Shutterstock

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Manufacturing News

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos