Manufacturing Modernisation and the critical role of technology – keynote speech by Goran Roos

Where are we going in this world? Well, if you look at this scenario, we have everybody going digital, and generally looking at what's happened over the last year, we can say that we have gotten five years digitalisation in about five months.

There's a dramatic increase in the digitalisation of general manufacturing activities. The problem, of course, is that industry development generally is path-dependent. It is [influenced] at a structural level. You cannot establish operations for which there are no suppliers or customers in a given location. So the sophistication of the economy matters.

There's a dramatic increase in the digitalisation of general manufacturing activities. The problem, of course, is that industry development generally is path-dependent. It is [influenced] at a structural level. You cannot establish operations for which there are no suppliers or customers in a given location. So the sophistication of the economy matters.

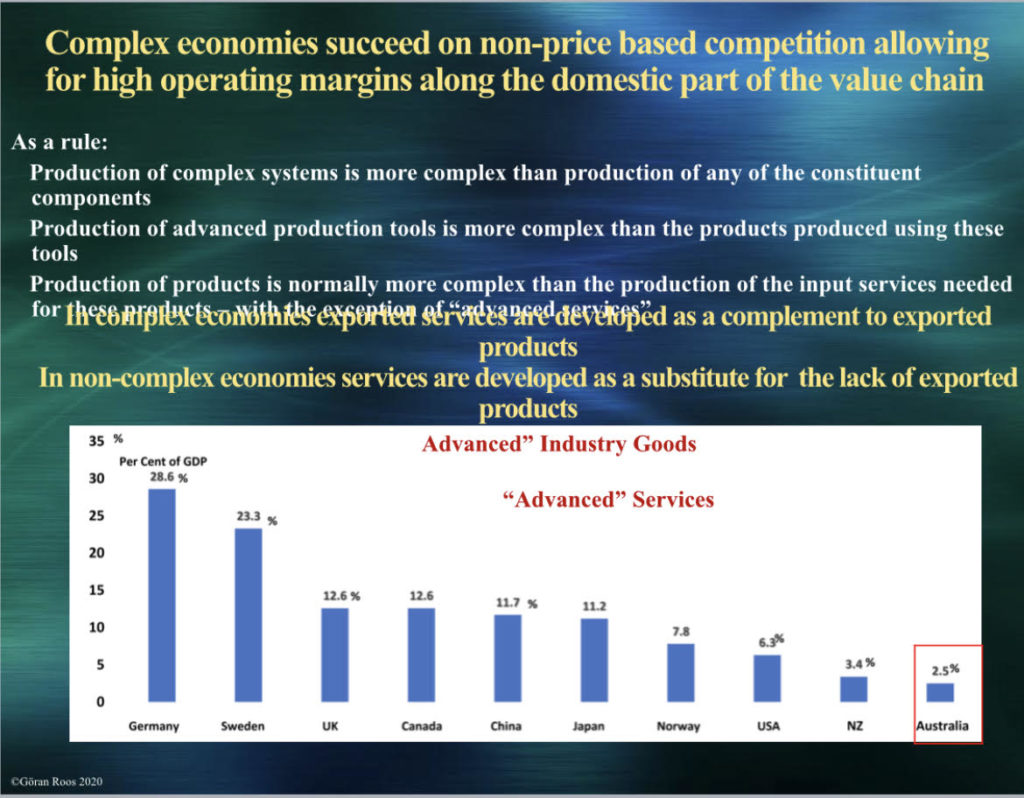

If we then look a little bit at where Australia sits in this world, we can see that the sophistication of Australia's manufacturing activities has declined quite substantially over the last number of years. Hopefully this will now change, but we can see that the past trends are not very good. And this has consequences. What it means is that in a sophisticated economy — in other words — people who are very high up on the previous graph, you can see that they generally compete not primarily on price. They compete on high operating margins along the domestic part of the value chain. And the reason they do this is they do very complex and difficult things that very few other people in the world are able to do. So if you look at this, you can see as a rule, the complex systems, be that a submarine or a car or something, is substantially more demanding than producing any of the components that make up that system. It's also a known fact that producing the tools that you need — the machine tools, 3D printers, whatever it may be — is substantially more demanding than producing the products using these tools. And finally, the production of products is normally more demanding than the production of the input services needed for these products, with the exception of what is known as advanced services.

If we then look at this more complex, we can see that in a sophisticated economy, as I said, you export services and you develop these services as a complement to the products we export. So in a very advanced economy, you may find that all the services that are exported, three quarters or so are linked to products that are also produced in that country, whereas in an unsophisticated economy, services are developed as a substitute for the lack of exported products. In other words, they may focus on things like tourism or similar types of services, which are not necessarily related to the products, but are a substitute for them. And that means that any sophisticated and prosperous economy is grounded in servitised advanced manufacturing, in other words advanced manufacturing that sells both products and the associated services. So if we look at the world, we can see what these things are. So if you look at advanced industrial goods, in other words, the ones that require a higher level of sophistication to produce, and we then add to that the advanced services that also require a high level of sophistication to produce, we can see that all the exported products as a per cent of GDP in Australia, this is around about two and a half percent.

To be compared, for example, to Germany with 28.5 percent. So there is some way to go in terms of Australia's ability to do these things and to grow its advanced manufacturing. Now some of these countries have for a long time focussed on manufacturing as a critical part of their economy, and others have realised that, generally speaking, over the last 12 months or so that manufacturing is a really good thing to have. Specifically, if you’re going to produce things like personal protective equipment, or you're going to produce maybe some critical equipment for your hospitals or some pharmaceuticals or associated activities. And that means that a lot of countries have suddenly started to develop industry strategies or industry policy, which previously was not something they cared very much about. And it's interesting to see this development. And of course, Australia is one of those countries where there is a need to improve the manufacturing sector. And government does have a role in providing those boundary conditions. And the new manufacturing strategy that has been presented recently is the first It's a small step, but it is a first step. So the good news is something is happening. The bad news, it is not necessarily very sophisticated in terms of a strategy as such.

To be compared, for example, to Germany with 28.5 percent. So there is some way to go in terms of Australia's ability to do these things and to grow its advanced manufacturing. Now some of these countries have for a long time focussed on manufacturing as a critical part of their economy, and others have realised that, generally speaking, over the last 12 months or so that manufacturing is a really good thing to have. Specifically, if you’re going to produce things like personal protective equipment, or you're going to produce maybe some critical equipment for your hospitals or some pharmaceuticals or associated activities. And that means that a lot of countries have suddenly started to develop industry strategies or industry policy, which previously was not something they cared very much about. And it's interesting to see this development. And of course, Australia is one of those countries where there is a need to improve the manufacturing sector. And government does have a role in providing those boundary conditions. And the new manufacturing strategy that has been presented recently is the first It's a small step, but it is a first step. So the good news is something is happening. The bad news, it is not necessarily very sophisticated in terms of a strategy as such.

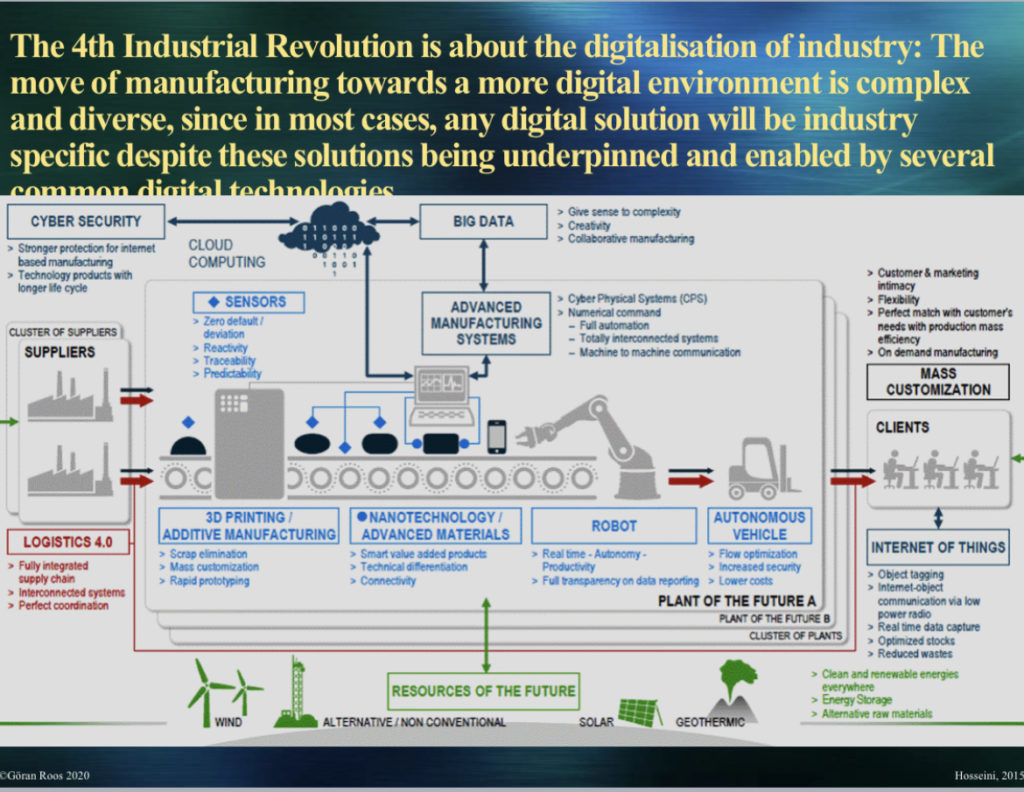

Now, if we then look a little bit on where we are heading in the digital world, everybody's heard about the fourth industrial revolution. And basically what that means is digitalisation of industry. Now, this sounds very simple and there is a number of common technologies underpinning it. The problem, of course, is that it is substantially more complex in practise than it might sound. And this is since in any given company, any digital solution will have to be industry-specific to cover all aspects of that company's operations. This is why you tend to find that digitalisation goes much faster in large corporations with high levels of capability and fine resources to draw on. Whereas in most SMEs, it is a real challenge to be able to have the capabilities and the money to be able to introduce all this technology in a meaningful way. And that can clearly be understood if we look at this somewhat complex picture. It illustrates all the things that will have to be thought about. When you look at digitalising a given manufacturing part, you have to think about the cybersecurity activities. You have to think about what things you want in the cloud and what things you want locally. You have to figure out what is the big data that you can use, how you get it and how you process it.

You have to have advanced manufacturing systems, which have been fully automated and totally connected, and machine to machine communication all the associated software to make on-the-run analytics. You have to have all the tools that are needed for these things, all the technologies, all the input in terms of advanced materials. You have to use maybe autonomous vehicles in your systems. You have to link to your suppliers and customers with digitalised logistics systems. You have to be able to mass-customise what you do. You have to have Internet of Things, to have the sensors in your product, and to work with all those things on an ongoing basis. You have to store the data, you have to process the data, and you have to make use of the data. And in addition to that, you have to use maybe materials that have a lower environmental footprint. You have to use energy that has a lower environmental footprint, in order to satisfy emerging consumer needs and requirements. So you can see that if you look at this, at a given specific company, it's very, very complex.

And if we then move on a little bit and say, ‘so what does it mean to move into this digital space? What kind of strategic questions do you have to ask?’ Generally, it happens in three steps. The first thing is you look at efficiency improvement. And that is how can I use these digital technologies to produce more for less? And this is fairly straightforward for most companies. This is what they have used new technology for, in different forms, for a long time. They know how to use technology to increase efficiency. So that's a fairly straightforward step.

And one of those efficiency focusses could be cloud computing, for example, which has some clear benefits to most companies in terms of efficiency.

And one of those efficiency focusses could be cloud computing, for example, which has some clear benefits to most companies in terms of efficiency.

The other dimension, which is more of a difficulty for many companies, specifically inside complex supply chains, is the effectiveness focus. In other words, to use digital technology to produce something that is more relevant and thereby more valuable to customers. And that requires using data on an ongoing basis to modify what you do and modify the product.

And you want to have these two things running. Then you can start to become a fully digitalised business, by developing your new digital business model, which is then how you will make value out of your data, what data you can collect, make sure that you own the data, transform the data and drive that towards value in these two dimensions.

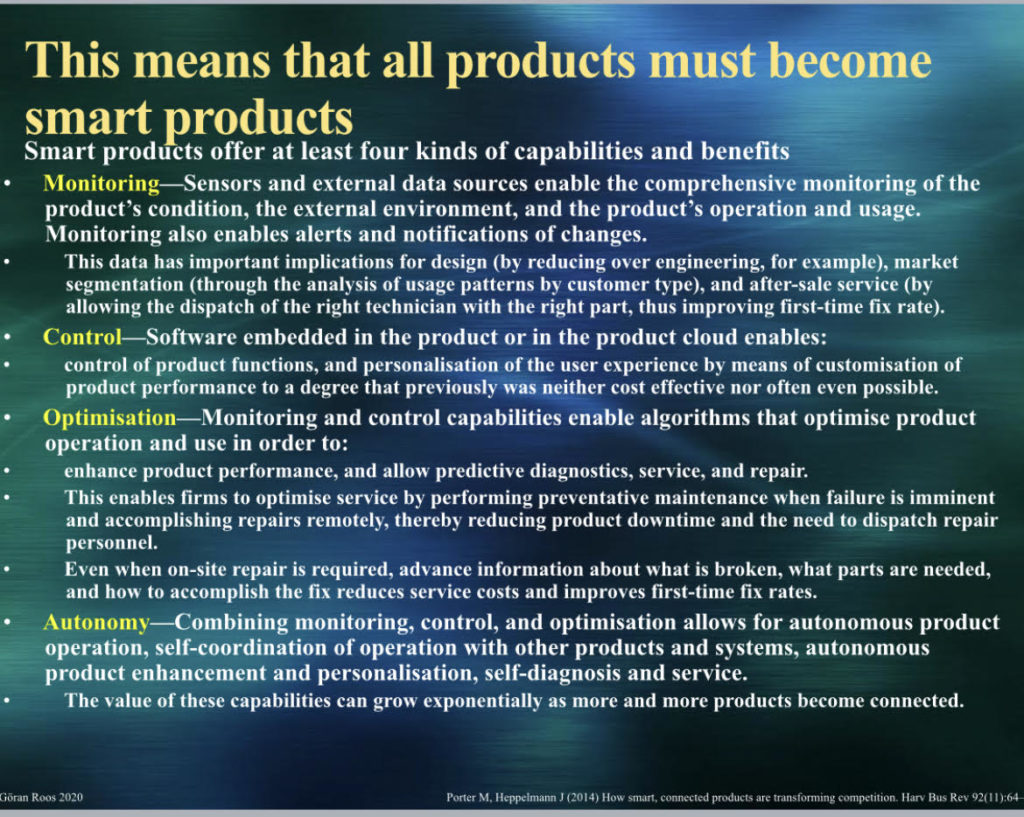

Finally, then, if we move into this, what does this mean for you as a manufacturer? Well, it means that all your products must become smart products.

You must build sensors into them to capture both the data about the product itself, as well as external data — it could be the temperature in which it operates or whatever it is. You then have to have software embedded in the product or maybe in the cloud, depending on the communication and latency issues. So that enables you to control the functions of this product at the given point in time.

Then, of course, you need to be able to optimise the product operation so that in a given context and at a given point in time, it is operating in an optimal way for its users, being the customer that you have. It also allows you to work with predictive diagnostics, predictive maintenance being one of the most rapidly growing parts of Industry 4.0 at the moment. And then, of course, ideally it should be able to operate autonomously from whatever else you do.

Then, of course, you need to be able to optimise the product operation so that in a given context and at a given point in time, it is operating in an optimal way for its users, being the customer that you have. It also allows you to work with predictive diagnostics, predictive maintenance being one of the most rapidly growing parts of Industry 4.0 at the moment. And then, of course, ideally it should be able to operate autonomously from whatever else you do.

So if we look specifically at this area of cloud ERP, which I know is quite interesting in this area, what do we know about that from academic research? We do know, generally speaking, that cloud ERP adoption, a good adoption of the right type of system, does have a positive influence on the competitive advantage of the firm. And I have given [a slide] — which I'm going to go through — three examples of research studies that illustrate these findings. Now, of course, one has to be very careful with these. One has to understand the context and understand what costs are involved, what the specific companies are, and their situation. But generically speaking and generally speaking, it does seem to have a positive effect.

And then finally, if we think of ERP in this Industry 4.0 world, what is it that we're looking at? Well, we have basically three groups of requirements from Industry 4.0.

One is the ability to balance the storage of data between a centralised and decentralised location.

There's something about managing the data flow in a two-directional way, both horizontal and vertical. And that means to be able to manage it together with legacy systems in this area.

Then there's something about data used in or sourced from virtual or real intelligent products. And here is where things come in like digital twins, there's something around the sensors that I discussed, and all these need to be reflected on.

And to finally say a few words about the complexity around this, as I alluded to before. If you look at a country like Germany, which generally is perceived to be extremely good at manufacturing — Industry 4.0 is very much a term that originated from Germany.

So what do we see when we look at Germany in this area? We see that the larger companies are well ahead in implementing digitalisation, but we also see that SMEs are well behind the average for implementing these things. So in a world that is very much emphasising manufacturing with a large, competent corporation, there's still a huge barrier, a huge hurdle for the SMEs to implement these technologies and to be able to put them to use. And this is a major challenge, because in some of these global supply chains, unless you as an SME are able to keep pace with the OEM and the customer in the necessary activities, you will be dropped from that supply chain. And to just give you an idea of some of the costs here, if you want to get hold of a piece of software that would enable you to be involved in the digital twin operations, for example, in the production of submarines, that would cost you around about between four hundred thousand and five hundred thousand dollars a year in licence fees. If you're a very small SME, that's a hurdle which is almost impossible to overcome, and that means that you would be excluded from being part of these things, in the critical components, by the mere fact that you are not able to afford the investment. And these are environments where governments have a critical role to play to enable those hurdles to some extent go away by either negotiating with the software suppliers or finding other boundary conditions they can impact to ensure that you do not exclude SMEs from the supply chains that we want to be a part of.

I will conclude with those words and I will happily take questions later on. But I would emphasise there is no choice in this. There is just a matter of how you do it and what scope you take. And with that, I wish you the best of luck in an interesting journey forward.

This is the keynote from Professor Goran Roos, given at the MYOB/@AuManufacturing event, Manufacturing Modernisation and critical role of technology, on November 25.

Picture: Goran Roos

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos