Our success in managing COVID-19, and why it matters when we talk about rebuilding manufacturing

By Sercan Altun

Prior to COVID-19 hitting the global economy in December 2019, Australia had already found itself in the middle of a trade dispute between the two superpowers: the USA, the long term ally on many fronts such as security and investment, and China, unstoppable rising power in Asia and the largest trade partner of Australia, imposing trade sanctions on each other’s goods and services due to the significant deficit worth of $419bn USD in 2018.

The wishful thinking from Australian governments was that the Australian economy would remain stable during these heightened tensions, given the surplus announced by the treasurer, and the belief that somehow cooler heads would prevail.

But then COVID-19 hit the global economy. Governments around the world started shutting down their economies and introducing measures not seen since World War 2. War economies were back on the agenda and $15 trillion has been spent by governments in a Keynesian style in response to the global pandemic. The questions looming in everyone’s minds have been how long this pandemic will be around and what will be the severity of the resulting economic havoc.

Like every single challenge it also brings opportunities to reflect on and learn from past mistakes, with the global pandemic laying bare Australia’s reliance on imports, and the frailty of international supply chains intensifying ongoing calls for a boost in Australia’s local manufacturing.

We have seen private companies all across Australia shouldering the burden by shifting to manufacture hand sanitisers, gloves, face masks, and more. Those heroes taking proactive action in Australia’s fight against this disease remind us that domestic manufacturing could address the shortcomings of supply chains built for just-in-time rather than just-in-case.

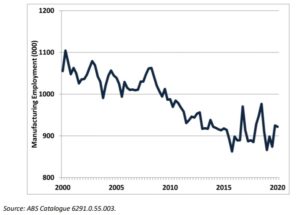

The latest report from The Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work ranks Australia last when it comes to manufacturing self-sufficiency among the OECD countries. It takes into account the volume of goods manufactured with those used in a given country. Australia manufactures two-thirds as much as it consumes, whereas most other OECD countries produce more manufactured goods than they consume.

There are different opinions as to why it has been the case, but the widely held view is that Australia as a high wage and resource rich economy has been unable to competitively manufacture. That belief itself has led to a nation that has one of the most underdeveloped manufacturing sectors with its tremendous untapped skilled workforce. What Australia should stop doing is relying on raw materials extracted from its soil such as iron ore and lithium being exported to its trading partners and the other exports such as higher education. By putting all its eggs into the export basket without having a self-sufficient manufacturing sector-based business model, the unsustainability of Australia’s economic sovereignty has been exposed by the trade tariffs imposed lately by its largest trade partner and resulted in a havoc wreaked on the complacency that has been going on for quite some time.

Lessons learned during the pandemic

The positive outcome of this global pandemic is that Australian state and federal leaders have put their ideologies and differences aside and heeded the advice of scientists leading in their fields. The second wave in Victoria that had recorded 725 new daily cases at its August 5 peak was eliminated albeit not eradicated, and the response was the envy of the world and saved thousands of lives.

Australian leaders should keep listening to our scientists when it comes to closing the gap in self-sufficiency in manufacturing with the other nations as well. If we were to look at any economically stable and successful countries on the world stage, one pattern in common would stand out: having a robust, sound and industrialised manufacturing sector producing value added products by investing constantly in new technologies.

For advanced countries with high labour costs, competing on cost is nearly impossible. To be able to keep their manufacturing industries thriving, a high-volume low-cost manufacturing mindset should be abandoned and a high-value low-volume approach — with customer- and export-focused manufacturing practices through Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), robots, Industrial IoT (IIoT) and the use of Big Data – must be adopted. Given the cost of these technologies decreasing and the high efficiencies they enable, Australia must adopt these technologies to gain a competitive edge, and state and federal governments must take action, such as helping manufacturers access capital to support this. Supporting advanced manufacturing technology adoption can also be facilitated through initiatives between public and private partnerships, and with other manufacturers that have successfully completed their transitions.

It is important to note that rapidly evolving technologies such as AI, ML, IIoT that have been reshaping the global manufacturing landscape will also reshape the Australian manufacturing sector, with major benefits such as creating many thousands of high-wage and high- skilled secure jobs urgently needed. Dr Jim Stanford of the Centre for Future Work estimates that raising self-sufficient domestic manufacturing to 100 percent could provide another $180 billion a year in new manufacturing output, increase GDP by $50 billion a year and create more than 650,000 direct and indirect jobs. Being the least self-sufficient OECD country must be a wake-up call and Australia should seize the opportunity and invest in advanced manufacturing techniques and practices to manufacture value added products rather than relying on the extraction of minerals.

It is important to note that rapidly evolving technologies such as AI, ML, IIoT that have been reshaping the global manufacturing landscape will also reshape the Australian manufacturing sector, with major benefits such as creating many thousands of high-wage and high- skilled secure jobs urgently needed. Dr Jim Stanford of the Centre for Future Work estimates that raising self-sufficient domestic manufacturing to 100 percent could provide another $180 billion a year in new manufacturing output, increase GDP by $50 billion a year and create more than 650,000 direct and indirect jobs. Being the least self-sufficient OECD country must be a wake-up call and Australia should seize the opportunity and invest in advanced manufacturing techniques and practices to manufacture value added products rather than relying on the extraction of minerals.

In this context, building a resilient and self-sufficient manufacturing sector will help close the gap with nations enjoying enormous growth rates.

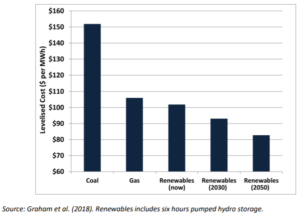

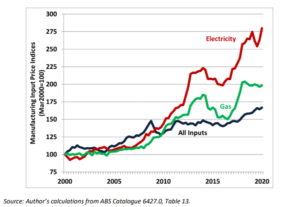

However, Australian manufacturers also need stable, cheap energy supply options such as renewable energy, especially given its competitive advantage in renewable energy sources, unmatched in the OECD.

By investing in renewable technologies, Australia will be able to have a reliable energy that keeps the lights on and contributes to net-zero carbon emission targets by 2050 as per Paris Agreement. Other OECD countries will find this more difficult to do — while maintaining constant growth — due to their dependence on fossil fuels. They will be forced to make a binary decision between growth and reducing their carbon footprint. This also comes with the price of losing their current attractiveness when it comes to foreign investment. Australia can blaze a trail for other nations competing to achieve both targets and kill two birds with one stone to achieve not just its economic recovery but also its net-zero emission targets around mid-century.

By investing in renewable technologies, Australia will be able to have a reliable energy that keeps the lights on and contributes to net-zero carbon emission targets by 2050 as per Paris Agreement. Other OECD countries will find this more difficult to do — while maintaining constant growth — due to their dependence on fossil fuels. They will be forced to make a binary decision between growth and reducing their carbon footprint. This also comes with the price of losing their current attractiveness when it comes to foreign investment. Australia can blaze a trail for other nations competing to achieve both targets and kill two birds with one stone to achieve not just its economic recovery but also its net-zero emission targets around mid-century.

Given the public awareness of the importance of the local manufacturing, Australian leaders should seize the opportunity and come up with ambitious and realistic goals to revive the domestic manufacturing sector, taking an active role in investing in advanced manufacturing techniques and practices, giving the support needed by our domestic manufacturers in their transition, finding new overseas export markets by using its industrial relationships with diversity mindset rather than relying on the largest trade partner, and doing away with the ‘just-in-time’ practices no longer viable for our manufacturers. It will require a fundamental mindset shift, new approaches to the current business models and new tax and regulatory policies to encourage local manufacturing to get back on its feet.

Given the public awareness of the importance of the local manufacturing, Australian leaders should seize the opportunity and come up with ambitious and realistic goals to revive the domestic manufacturing sector, taking an active role in investing in advanced manufacturing techniques and practices, giving the support needed by our domestic manufacturers in their transition, finding new overseas export markets by using its industrial relationships with diversity mindset rather than relying on the largest trade partner, and doing away with the ‘just-in-time’ practices no longer viable for our manufacturers. It will require a fundamental mindset shift, new approaches to the current business models and new tax and regulatory policies to encourage local manufacturing to get back on its feet.

In the final analysis, the outlook picture for the revival of local manufacturing seems rosier than ever. Like the success achieved in taming the virus and getting back to a new normal by heeding the health advice from our scientists and healthcare workers, Australia needs the same success story in its domestic manufacturing sector. At the end of the day, Australia needs a strong, self-sufficient manufacturing sector for its own economic sovereignty and the security of its society.

Sercan Altun is an electronics engineer and technical sales engineer at Pepperl+Fuchs (Australia) with extensive knowledge in the field of digitisation of production systems, the industrial internet of things (IIoT) and advanced manufacturing processes. Pepperl+Fuchs is a company specialising in factory and process automation.

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Analysis and Commentary

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos