Underwater robotics maker grasps new opportunities

By Brent Balinski

Tucked away on a residential street, spitting distance from a lively bistro pub in Glebe (about three kilometres from Sydney’s CBD) is where you will find the most promising Australian robotics manufacturer you’ve never heard of.

“I like being in the city, and I like being close to the universities,” Paul Phillips co-founder and CEO of Blueprint Lab, tells @AuManufacturing.

“It does cost more in terms of rent, but I think it's a trade off.”

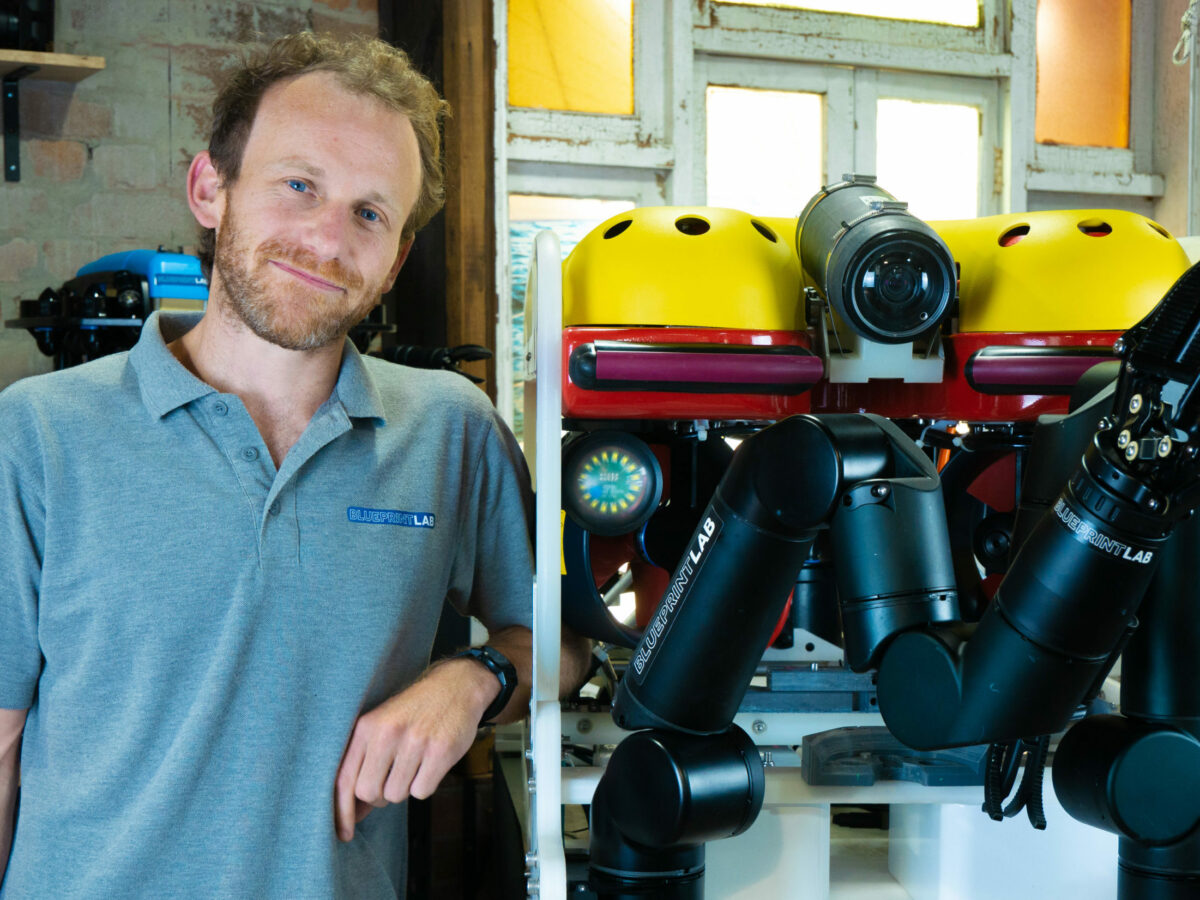

Phillips (pictured) says his company has nearly doubled in size the last year, with the headcount now at 31. It exports 95 per cent of what it makes: two models of robotic arm in different variants, as well as end effectors such as grabbers, controllers, software, and related accessories.

Their robots’ applications are mainly in the dangerous part of dull/dirty/dangerous, such as inspection of oil and gas and other offshore energy assets.

Blueprint plans to get its arms into all sorts of scenarios, but they found their first market among underwater remotely operated vehicle (ROV) operators.

Phillips did subsea ROV arm work (which was never commercialised) as a mechatronics engineering intern with a small company in WA named Sea Tools. A few years after that, he reconnected with Sea Tools, asked the owner if ROV arms were worth pursuing, and was told yes. Phillips started Blueprint in 2016 with Mark Sproule, a former mechanical engineer at ResMed.

He was put in touch with a potential client in Seattle working on an undersea vehicle for the US Navy, made a first sale, and Blueprint has grown since. Robot arms for ROVs are a niche within a niche, but were apparently worth pursuing.

At a low level

Why underwater manipulation, of all things?

“At the previous job where I worked, we were building stabilised camera systems for UAVs and that was also a very complicated electromechanical system. And I saw… evidence that there was a market need for robotics,” explains Phillips.

“I felt like I had at least the basic knowledge of how to get started, and I witnessed first-hand a company be successful through developing something that was very complicated. And unlike an app, [which] investors love – but there's also one in a million times you’re going to make it – this is sort of very limited competition.”

Phillips says Blueprint has innovated in many ways around its arms, and designed and manufactured from “as low a level” as required. This has included patented electric actuators as an alternative to clunky, heavy hydraulic ones (and allowing for the smallest robot arm of its kind), novel joint designs for waterproofing, “and now we're even going to the extent of building our gearboxes and custom motors.”

“You have to remain competitive,” he adds.

“It’s a niche industry and there’s going to be a few players globally who can remain competitive. And we need to be able to invent things that keep us ahead.”

To the moon

Applications so far have included infrastructure management, scientific sampling and university research. More recently, Blueprint has moved out of the water and into projects in the nuclear industry, defence – integrating a manipulator onto BIA5’s autonomous ground vehicles – and space.

Earlier this month it was awarded a $318,000 grant in round four of the Moon to Mars Supply Chain Capability Improvement Grants.

An ambition early on had been to make robotic arms for space missions, says Phillips, but it’s a slow-moving industry, especially when it comes to sales.

“And that's really the issue for us, because we're a company that's built on selling products, not just raising money,” he adds.

The Moon to Mars grant is “essentially a gap analysis” that will examine what would be needed to make a manipulator space-suitable. Vacuum operations are not so big an issue, but temperature fluctuations are a consideration, as is radiation as trips get further away from earth.

Initial testing is currently being lined up with University of NSW and UTS.

Larger-scale projects of all kinds will be aided by a yet-to-be-announced acquisition by the London-headquartered General Oceans, believes Phillips.

It will bring in the resources to work on larger-scale projects and speed up product development, says the founder, taking the company “to the next inflection point: more access to capital, more access to expertise beyond my sort of level.”

Skills shortages

The two biggest challenges during the Covid era have been – perhaps unsurprisingly – electronic component and skills shortages.

According to a report released this month by Engineers Australia, job vacancies across the profession reached a ten-year high in 2021. Australia also has one of the lowest ratios of engineering graduates relative to other degrees in the OECD.

As a way to address the skills issue, Blueprint has kept strong links with nearby universities, running internship programs, supporting societies, holding open days, and recruiting talented grads.

“This company has really been built on hiring graduates, just because there's limited people in Australia with experience in this field to begin with… But as we've grown, there's been a need for people with more experience, and not having access – either for ourselves or other companies – to engineers from overseas has really left a huge void in the job market in Australia,” says Phillips.

“Where we used to have 200 applicants, now we get 20. And it's been challenging. But so are many other things to growing business. It's just another one [laughs.]”

Pictures: supplied

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Analysis and Commentary

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos