Which jobs are most at risk from the coronavirus shutdown?

Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, University of Melbourne

The immediate impact of the coronavirus shutdown is striking in its magnitude, its speed and its concentration on a small set of industries.

My attempt to identify where the virus and the shutdown will have the biggest effect suggests that in February 2020 about 2.7 million workers were employed in the most exposed industries.

And while it won’t be possible to know for sure until April 16 when we get data from the Bureau of Statistics on the labour force in March, I believe it’s reasonable to think the jobs of about 900,000 are already under threat.

Which jobs are most at risk?

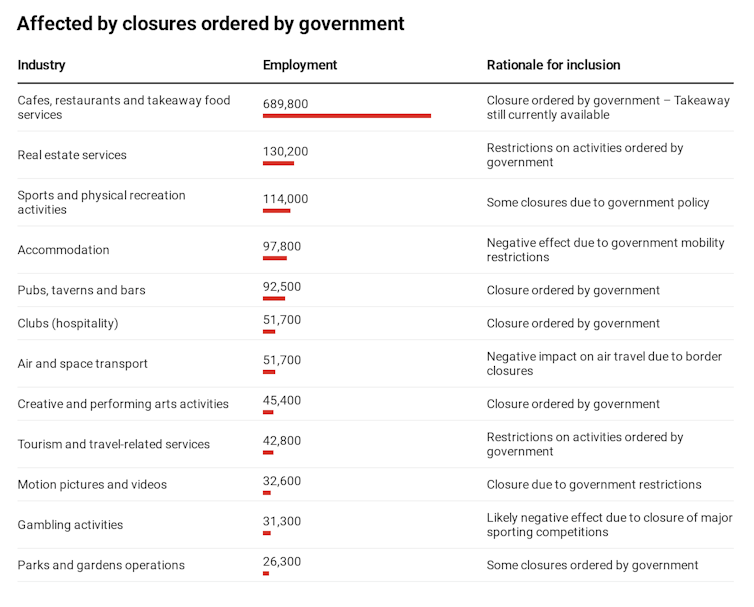

In the table below I list those whom I think are most at risk.

For one group of about 1.4 million workers – primarily in industries involving eating out, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and air travel – the loss of work is the inevitable result of government shutdowns.

ABS 6291.0.55.003

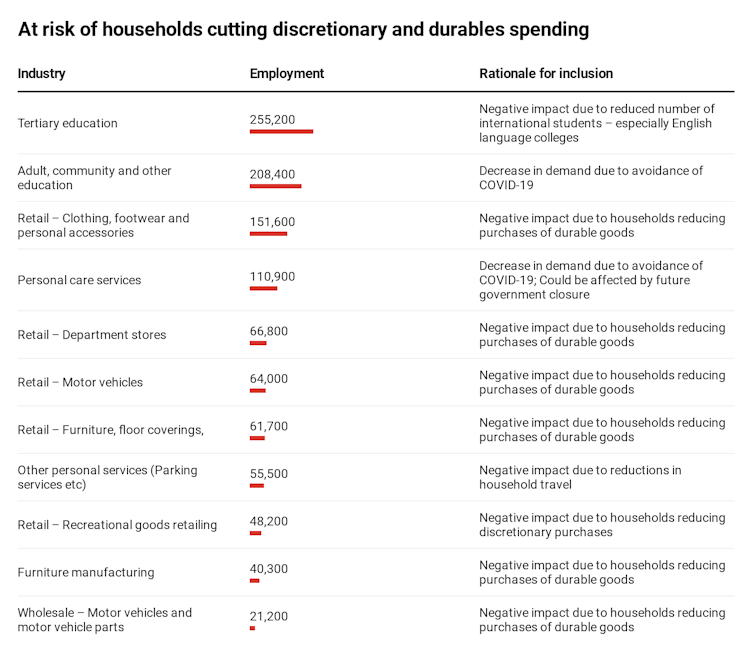

Another group, comprising about 900 thousand workers, are in retail trades (non-food) and personal services, where the effect on jobs is coming from consumers cutting spending apart from on essential items.

ABS 6291.0.55.003

Workers in both at-risk groups are predominantly young. More than half are under 35 years of age. Six out of seven are employees. About one in every seven is an owner/manager or works in a family business.

A slightly higher proportion are female than male. They are evenly split between full-time and part-time.

Some industries will grow

Some industries are seeing rapid increases in demand due to the coronavirus. They include the retail grocery trade and associated logistic services, and the supply of office essentials needed to work at home.

In a relatively short period there is also likely to be an increase in demand from the health care and health services industries.

Other areas where increased demand seems likely are the home delivery of goods bought online, cleaning services and services usually undertaken by volunteers and government agencies who are occupied dealing with COVID-19.

The total workforce will shrink

So far there has been little impact of the supply of workers, but it will happen.

It is beginning to occur as schools and childcare centres close and workers withdraw in order to care for their children, and it is accentuated by parents not wanting to risk outsourcing the task to grandparents.

In the coming weeks, there will be further hits to labour supply as illness from COVID-19 causes workers to need to take leave and other workers withdraw to provide care for family members who become ill.

It is difficult to be precise about the magnitude of withdrawal from the labour market, but it is potentially large.

To start with, most of the impact is likely to come from withdrawal for caring or to avoid illness.

As an indication of the potential scale of withdrawal, in 2019 there were 1.21 million families with children aged from 0-9 years in which either a sole parent or both parents were in paid work.

In 2016 there were 634,500 people aged 65 to 84 doing voluntary work.

Workers becoming ill might also have a substantial impact on labour supply.

Under a (hopefully pessimistic) scenario that COVID-19 continues its current rate of growth over the next three weeks, with those infected in the previous two weeks then unable to work, this would be about 67,500 persons out of work due to illness.

COVID-19 has already had a dramatic effect on employment – that much is evident from news images of queues at Centrelink.

Further impacts are almost certain in coming weeks.

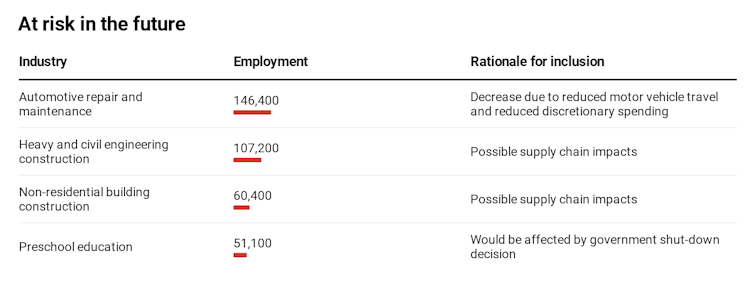

ABS 6291.0.55.003

The scale and speed of what’s happening is creating the most serious labour market policy challenge of the post-war era.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured picture: People queuing outside Centrelink office in Bondi Junction, Sydney on Tuesday. Joel Carrett/AAP

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Manufacturing News

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos