30 years on, we still haven’t got industry policy we need

By Peter Roberts

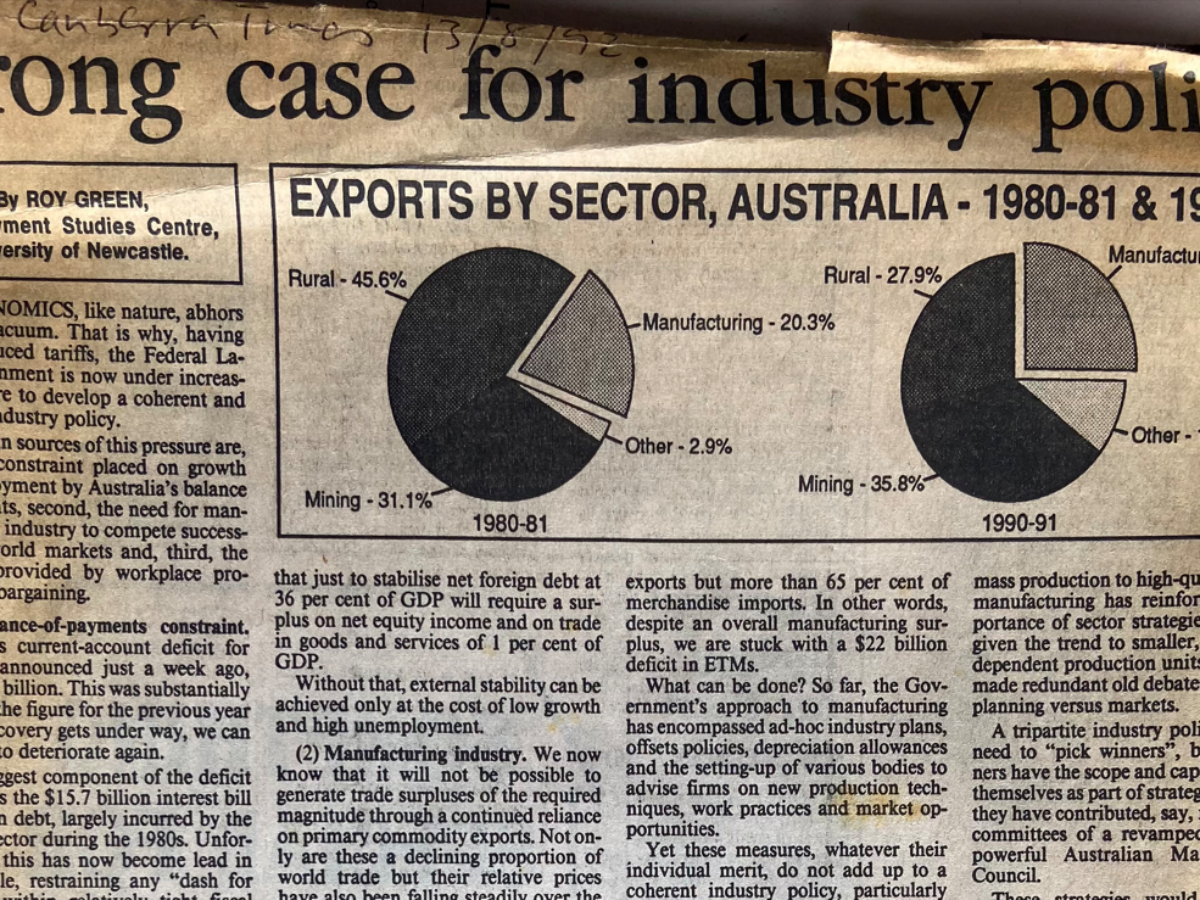

A week or so from now, 30 years ago a young warrior for manufacturing industry Dr Roy Green had this article (pictured) printed in the Canberra Times outlining the case for a national industry policy.

Australia was then just emerging from a ‘sheltered workshop' era of manufacturing as the then Labor government unwound protection sometimes exceeding 200 percent that had created a derivative, technologically laggard manufacturing sector.

The need for national policy to direct business innovation into high value elaborately transformed manufactures (ETMs) – the fastest, growing, most valuable areas of world trade – was as obvious then as it is today.

The only caveat being that the mineral boom of the 2000's temporarily postponed the reckoning Australia now faces with its lack of economic complexity, extreme dependence on overseas – often Chinese – supply chains, and its reliance on undifferentiated commodity exports – today's being coal, gas and iron ore.

I know this because I have spent much of my journalistic life reporting on Roy Green's analysis and predictions, both at the Australian Financial Review for 27 years and lately, at @AuManufacturing.

Roy has received the positive judgement of his peers becoming Dean of the Macquarie Graduate School of Management and Dean of business at UTS, Sydney business school, and has been listened to by governments – but only so far.

In his Canberra Times article he talked about strengthening the institutions fostering innovation, productivity and globally focused growth – specifically the then Australian Manufacturing Council.

With the AMC, and its companion the industry-analytical Bureau of Industry Economics, both killed off, leaving only the ultra dry and superficially theoretically correct Productivity Commission still standing, we are further away from a rational industry policy than we have ever been.

The $20 billion balance of trade deficit overall Green talked of 30 years ago has been replaced by a $50 billion plus trade deficit in only one category of manufacturers – transport equipment. In ETMs the trade deficit is well over $100 billion – and it has to be paid for somehow.

The destruction of the car manufacturing sector really stands out at the latest, dumbest shot in our own foot of the recent, and increasingly unlamented Coalition government.

How could we have been so stupid – what, we are going to permanently rely on imports for every single of the million cars we buy each year? Forever?

How to get a car industry back, this time a forward-looking electric vehicle industry, has to be an early goal of industry policy.

But more fundamentally Roy Green wrote in @AuManufacturing in 2020 of the five building blocks of industry policy:

First, we must overcome the fragmentation and under-resourcing of institutional policy-making in Australia.

Funding for research and innovation, for example, is spread haphazardly over 13 portfolio areas and 150 budget line items.

A new National Industrial Strategy Commission should be established to develop national priorities in consultation with industry sectors, aimed at growing “industries of the future” with new technologies and business models.

…Second, there has been a longstanding, widely acknowledged need to deepen collaboration between industry and research organisations, possibly around designated “national missions”.

This will require an immediate reversal of the decline in both government and business expenditure on research and innovation, now far below the OECD average at 1.79 per cent of GDP, and still falling against the trend elsewhere.

It will also require funding agencies to address the research mismatch between industry and universities. Recent data indicate that while funding is relatively abundant for health and medical research, enabling Australia to grow a world competitive “medtech” and pharmaceutical sector, it is hopelessly inadequate for engineering and information technology, which is essential for more broadly based manufacturing.

…Third, we should not overlook the contribution of entrepreneurial startups to economic recovery and renewal, including integration of the digital and physical dimensions of manufacturing, which is a key feature of Industry 4.0. Governments everywhere facilitate startup activity, as well as scaling up new ventures for global opportunities, through support for innovation precincts in cities and regions.

This is where the division of responsibilities between Commonwealth and States becomes relevant, currently a microcosm of system failure. While the Commonwealth’s role is to establish a robust, properly funded national policy framework, the States should carry much of the responsibility for delivering business services and infrastructure, particularly for industry clustering and place-making initiatives.

Fourth, the Government can also make a big difference for small and medium enterprises with public procurement policy. Too often we see local tenders overlooked in favour of large international companies on a narrow “value for money” basis, when these large companies themselves might owe their existence to another country’s more imaginative procurement policy.

Measures like the US Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program are a powerful instrument for enterprise capability-building and the development of critical mass in local supply chains.

They can also supplement foreign direct investment attraction programs, when these are designed, as they should be, to enhance research intensive manufacturing at home.

…Fifth and finally, industrial transformation in Australia will depend ultimately on the adequacy of our workforce and management skills. The international evidence suggests that these skills are lagging other comparable countries, and that if anything they are atrophying further with the decline of manufacturing and the myriad of related services which contribute to economic complexity.

Hence, education and training must be a key element of industrial strategy, along with provision to draw on workers’ talent and creativity at the enterprise level. Again it is clear from the evidence that involving workforces in the range of decisions that affect them contributes to superior productivity performance, so why wouldn’t we encourage this practice, or even mandate it?

Most immediately, substantial public funding will be needed to repair the damage to the TAFE system from market contestability, and to place vocational education and training at the heart of the strategy to rebuild manufacturing capability.

Green's article then was part of @AuManufacturing's crowd sourcing a new deal plan for manufacturing from our readers and members, and this remains a valuable guide today.

Thanks to Roy Green, we have always known what to do, and we do so still today.

Picture: Canberra Times

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos