Things picking up for Sydney sensor business

UNSW spin-out Contactile won the Advanced Manufacturing category at last month’s Australian Technologies Competition. Brent Balinski spoke to co-founder Heba Khamis about making robots feel like we do.

If you asked, a robotics researcher might tell you that their field is a long way off delivering on the promises of famous science fiction yarns.

As the Australia Centre for Robotics Vision director, Professor Peter Corke, put it this year, computers have beaten people at chess and Go, yet, “We don’t have a robot that can reliably pick up a chess piece, which a child could do.”

Human-level dexterity for robots remains a holy grail. One contributor to this situation is the complexity of our sense of touch, says Dr Heba Khamis, a biomedical engineering lecturer at University of NSW and CEO/founder at sensor startup Contactile.

One of the company’s developer kits, which comes with two 3×3 sensor arrays, a communications hub for power and data acquisition, and software.

(https://contactile.com/products)

She estimates there are maybe 10 or 15 research groups worldwide trying to understand touch — “by no means something that we’ve solved” — which is not simple to unpack.

“We use visual feedback to move the arm to where it needs to be, we use proprioceptive feedback so we know where our joints are in space — we use that to figure out if it’s in the right position — and then when we try and pick something up. As soon as we touch it, we kind of switch over to relying on our tactile feedback,” she tells @AuManufacturing.

“It is on its own a very complicated system, And then, adding to that as well, the feedback mechanisms that humans employ when they are interacting with things — that’s another layer of complexity because we not only use the feedback, but we also have feed-forward mechanisms.”

You pick up that bottle of water you set down earlier, and without being totally conscious of it, you’re thinking of how heavy it was and adjusting your approach, and during the act you’re correcting any errors in prediction you might have made.

And if you’re not convinced of the importance of touch, she adds, consider that there are some 2,000 receptors on your finger pad. They would not have proliferated if they didn’t provide an evolutionary advantage.

Contactile is commercialising work that tries to understand and borrow from the biomechanics of our fingers to build more capable robots.

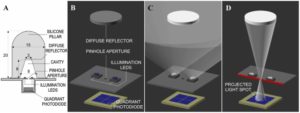

Its sensor arrays are inspired by finger pads. Each unit is instrumented to detect changes in light inside a hollow silicone pillar as pressure is applied on it. These changes are used to infer changes in 3D deflection, force and vibration

Khamis, who earned an engineering PhD on diagnosing epileptic seizures from EEG signals, had been working on tactile sensors since 2014. With Contactile co-founder Dr Stephen Redmond, proof-of-concept sensors had been developed, but Khamis credits the “genius” instrumentation work by Benjamin Xia (now CTO and then an electrical engineering student) with making the system as practical as it is.

“The way that the light instrumentation works, inherently has already got all those properties, such as the electronics, which are completely separate from the thing that physically interacts, that makes contact, which is very beneficial because it means that it can be easily made waterproof, chemical proof, etcetera etcetera” she explains.

“You can easily replace the silicone if it wears down because it’s completely separate from the electronics. It’s just silicone, so it’s cheap.”

Illustration of sensor from “A novel optical 3D force and displacement sensor – Towards instrumenting the PapillArray tactile sensor” paper (Sensors and Actuators A: Physical,

Volume 291, 1 June 2019, Pages 174-187)

In late-2018 the trio realised it was time to spin the company out of university. They had promising research, though no industrial partners to transfer the technology to and their university — the owner of the IP — needed justification to put up the cost of patenting and protecting this.

Khamis’s company has achieved recent wins as Startup of the Year at the NSW iAwards (the national final is tomorrow) and in the Advanced Manufacturing category at last month’s Australian Technologies Competition.

It has sold some of its developer kits to universities, and is currently assembles in small volumes in-house. The team uses a lot of 3D printing, pours its own silicone, and has printed circuit boards made under contract, says Khamis, and is in talks with potential investors and commercial partners as it looks to push its solution into the world and to scale up.

She believes a sense of touch could help improve a large number of robotics applications, from warehouse logistics to fruit picking and beyond. Whether you’re turning a door handle or opening a bottle or turning a valve, it’s all the same kind of manipulation, says Khamis. All the fingers need to do is hold on.

“Picking stuff up is is all well and good because there’s lots of applications where you need to pick up a variety of objects and you don’t know in advance what the properties of those objects are, and this is obviously very valuable in that scenario,” she says.

“But the kind of next stage of that is what about performing other functions in these unstructured environments. Really kind of long-term vision stuff is like ‘what about remote autonomous maintenance of satellites in orbit?’ So it’s holding tools or, you know, turning things and all these different types of action that essentially require the exact same functionality.”

Featured picture: Visual Content Team, UNSW

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos