Tiny Perth startup takes on medical moonshot

A Perth startup is developing an approach to pumping that could find a way into artificial heart implants. Brent Balinski spoke to its founders about the ambitious project, and about trying to solve really big problems within Australia.

In 1969 the Apollo program put the first man on the moon. The same year, the Texas Heart Institute in Houston put the first total artificial heart in a man (he lived 64 hours, received a heart transplant, and died shortly after.)

Mechanical circulatory support has come a considerable way in 51 years, but a reliable total artificial heart remains a medical moonshot.

It is the only organ you can’t live without. Next to the brain, the heart might be the trickiest organ to emulate mechanically.

A tiny startup in Perth founded in 2017 and named Astronova is taking its first steps towards what might one day enable a new kind of TAH, based on a novel type of rotary displacement pump. Daryl Wheeler and his father invented the core concept for fluid transfer in the 1970s, and it has been successfully applied in moving slurry at mines, in desalination, in automotive fluid motors and elsewhere.

The first artificial heart, implanted by surgeons Domingo Liotta and Denton Cooley into Haskell Karp in 1969. (Picture: The Atlantic)

“It runs very slow and at very low RPM has a high flow (output) and efficiency,” Ben Wheeler, CEO of Astronova and Daryl’s son, tells @AuManufacturing.

“There are a lot of other technologies, which need to run at high RPM to get the [necessary] flow.”

According to the company, their pumping system produces low shear stress and turbulence – handy when moving a sensitive substance such as blood.

They also say the efficiency levels achieved in lab trials point the way to smaller devices, which could be fully implantable. Current circulatory assist products use an external driver, and drivelines running through the body pose a risk of infection.

“Imagine how exciting it is to see an amazing new pump and think ‘wow, this can really solve a host of blood pumping problems, from circulatory support right up to LVADs [Left Ventricular Assist Devices] and Total Artificial Hearts?’” Dr Greg Roger, a doctor and award-winning Australian medical technology inventor, told @AuManufacturing last year. (Roger is now also a director at Astronova.)

“In the next 12 months, we'd like to have a lot of benchtop testing and we'd like to have some early stage animal trials to assess its ability to demonstrate what we believe is true,” adds Wheeler.

Time and money

Daryl Wheeler first received the curiosity of surgeons in the early 1980s after presenting on his fluid transfer concept at a conference in New York. He credits “bumping into” Roger a few years ago and brokering an introduction to cardiothoracic surgeon Mike Wilson for the early progress of this venture.

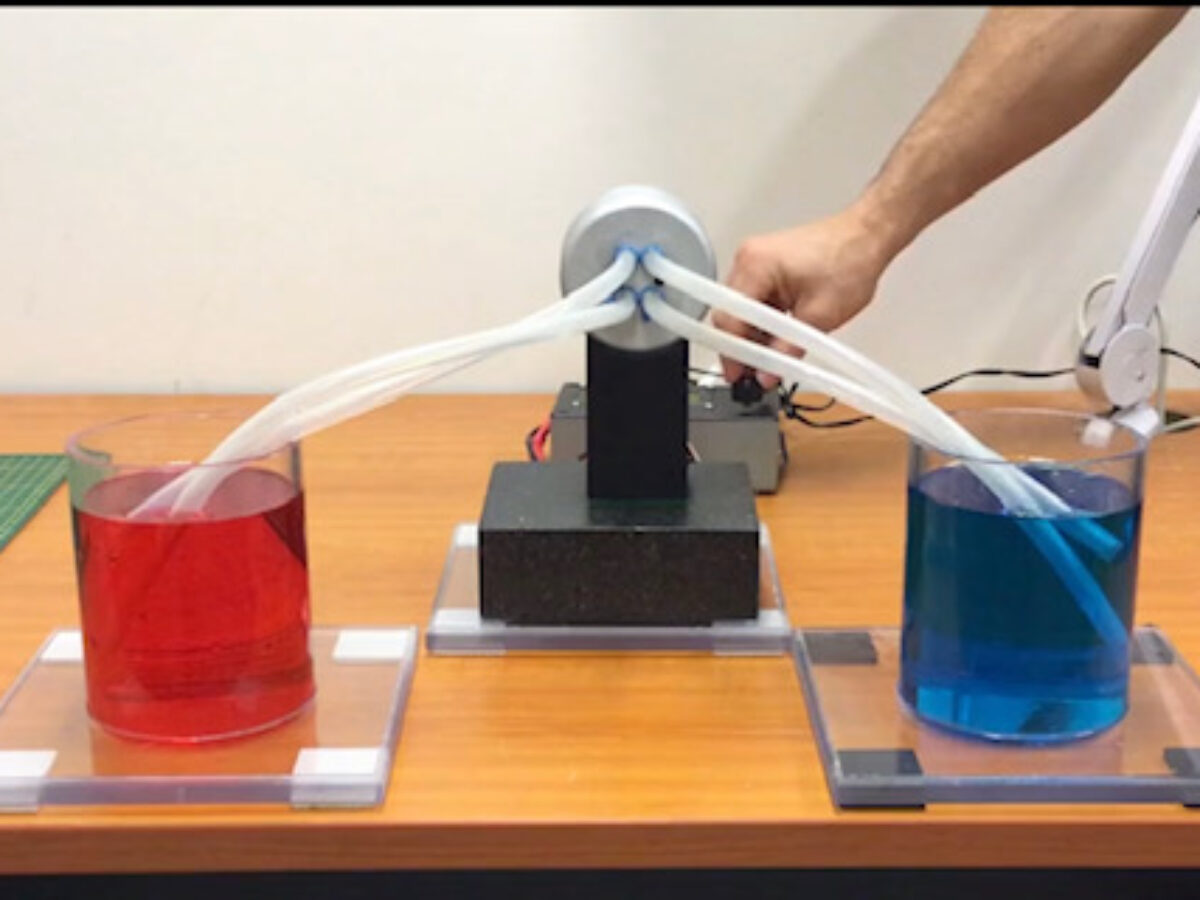

A prototype of the core technology in a mock circulatory loop, using a mix of glycerol and water as a fluid, was later rigged up at the ICET Lab at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital.

The company has also formed collaborative relationships with ICET, Monash University’s Baker Institute, and Perth’s Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research.

The first application Astronova is working towards is an implantable device to treat critical limb ischemia, a severe obstruction of arteries due to plaque reducing blood circulation to the extremities.

“Generally amputation is the only option,” says Wheeler.

“We could move and that could go into market within four to six years.”

Higher-hanging fruit includes ventricular assist devices, which he estimates would be a minimum of eight to ten years, and a total artificial heart, which would need over a decade of development.

He adds that a ventricular assist device is a difficult undertaking, and a project would require a budget of perhaps $300 million to $500 million.

“When you talk about Australia and capital raising… Australia's financial position and ability to fund projects like this is incredibly short-changed,” Wheeler suggests.

Commercialisation within life sciences is generally an expensive and time-consuming affair. Lorraine Chiroiu, the CEO of AusBiotech tells us that this is a function of the complexity of the science and regulatory requirements, and different business cycles.

“It is highly regulated, usually requires expensive clinical trial data before any product can be approved, and has longer than usual development times,” she tells @AuManufacturing.

“Products can often take around five to eight years for medtech products to come to market, and between 10-15 years and up to $2.5 billion to bring one biopharmaceutical product from early research to market, with little or no revenue.”

Picture: Bivacor

Australia can claim the inventors of the pacemaker in the 1920s. It can also claim the inventor of a total artificial heart, Dr Daniel Timms, who has been developing his maglev spinning disc-based device since 2001 and his PhD at Queensland University of Technology. His Bivacor (pictured left) has so far been trialled in cows and sheep, and is nearing human trials.

Bivacor is a research partner with the Texas Heart Institute, is incorporated in Delaware, and has its engineering HQ in Los Angeles.

The pools of talent and investment dollars required to bring such a complex device to market are deep, and probably don’t exist here.

The largest life sciences VC fund under management in Australia, Brandon Capital’s Medical Research Commercialisation Fund, is $251 million. That total amount is less than Wheeler’s estimate for developing a ventricular assist device.

Worth the trouble

As promising as their concept is, Wheeler concedes the likelihood of designing and manufacturing an entire artificial heart here is small. The resources required are just too great.

“The vision that we get is… some large medical group that has billions behind them will roll along and pick you up somewhere along the line and take it over from where you've left off,” he says.

So, do Australian companies have the capacity for long-termism? It depends who you ask.

The problem of cardiovascular disease, which kills nearly a third of all humans, is clearly a focus for CSL (ASX:CSL). The R&D leader (its bill for the last five years is $US 3.3 billion) has been developing CSL112, a plasma product treating heart attack sufferers, for two decades.

The Sydney Morning Herald reported last month that, “7,000 heart attack patients have now taken part out of a eventual pool of 17,000 subjects for its phase-three trial, which it launched in 2018 and estimates will cost up to $800 million.”

It’s arguable that the country needs more CSLs, more Cochlears, and more Resmeds.

Benchtop tests at ICET

Wheeler agrees that more needs to be done to encourage companies to pursue the really difficult, really valuable ideas.

“If not, we’re going to be a country that falls behind countries like the U.S. that are supporting it and China and Japan,” he says.

“They're all countries that see an importance in inventiveness and advancement. And if we get stuck in Australia, just digging holes, I think we're going to fall behind.

His father Daryl concurs.

After a long career as an inventor, he believes that any current attention being paid to IP-based startups is quite new, and the infrastructure and capital to support the people with big ideas isn’t there yet.

“And when we move into medical, it becomes even more complicated, because we're dealing with academia, universities, medical, fraternity and industry and government, often as well” he says, adding that demand for our top export, coal – predicted to be $67 billion this financial year – won’t be there forever.

“It is hard work doing mining as well, but there's a laziness to it. You just dig stuff up out of your backyard and sell it to somebody and often don't even add value to it. We're a young country that really hasn't sorted out how to mature in that way yet. So we're part of trying to make change, that's what it's about as well.”

Pictures: astronova.com.au unless otherwise stated

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos