@AuManufacturing![]() and AUS-Semiconductor-Community’s editorial series, Australia’s place in the semiconductor world, is brought to you with the support of ANFF.

and AUS-Semiconductor-Community’s editorial series, Australia’s place in the semiconductor world, is brought to you with the support of ANFF.

Australia’s place in the semiconductor world: Defence could be the new champion for a sovereign microchip industry

Today our Australia’s place in the semiconductor world series looks at ways Australia can address its precarious dependence on overseas chip suppliers, and the role of defence in this. There is no time to waste, argues Martin Hamilton-Smith.

In March 2023 the Albanese government’s Defence Strategic Review will be handed down by Sir Angus Houston and Professor Stephen Smith. Nothing is off the table. Sovereign capability will be at the centre of the report and in the mix will be the dilemma of semiconductors.

The problem is self-evident. We can afford to be in defence reliant, but not dependent, upon foreign governments and overseas manufacturers, even our closest friends.

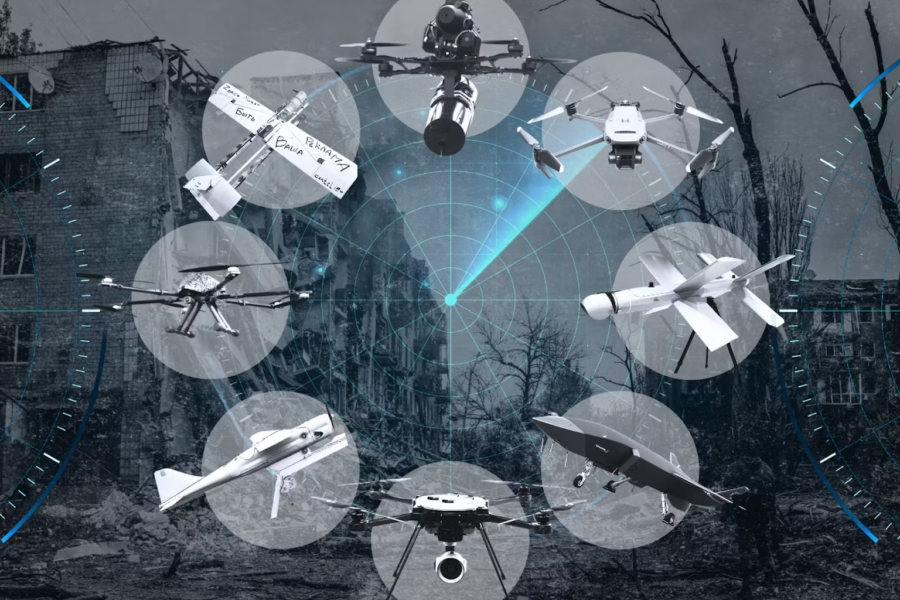

The submarines, warships, aircraft, vehicle, communications, and other systems the ADF operates are built and maintained using millions of advanced microchips. The difficult truth is that to be genuinely self-reliant and sovereign, we need an ADF with command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (C4ISR), and ships, aircraft, vehicles of all forms and combat systems which can be independently operated, maintained, repaired, upgraded, under Australian government control.

The bountiful supply of the latest microchips we presently import come from dangerous strategic hotspots along vulnerable lines of supply, made even more tenuous in the event of a military conflict. Even our allies and friends will prioritise their own needs ahead of ours in a strategic crisis; we learnt that during the pandemic.

That means Australia needs a microchip design and engineering capability if we are to survive a crisis.

Our microchip problem is exacerbated by a local industrial ecosystem of declining complexity, making solutions more elusive.

Australia’s manufacturing GDP share today is below 6 per cent, having declined almost continuously since 1995.

Australia produces the lowest proportion of manufactured products for its own consumption or use in the OECD, and Australia’s level of manufacturing self-sufficiency is also the lowest among OECD countries. Our import dependency centres on elaborately transformed, knowledge-intensive and complex manufactures.

This is correlated to dramatically declining economic complexity with Australia declining to levels of complexity typical of a developing country. In 2018 Australia was 87th of 133 in scope nations, a fall of 20 places over the previous decade.

Alongside the dramatic and absolute decline in the size of manufacturing should be noted its vertical disintegration.

The demise of automotive manufacturing, which had been Australia’s most complex vertically-integrated value chain, is illustrative of a broader trend. Australia’s remaining manufacturers are, for the most part, no longer parts of an onshore industry vertical – a large scale interdependent value chain of complex lead customer and tiered supplier relationships.

Within manufacturing itself, value chain linkages are now distant and import-dependent, and key value chain capabilities absent. Australia’s dependence upon imported microchips sits within this fault line.

Researchers and defence industry businesses depend on access to supercomputers to solve computational problems standard computers cannot handle.

The importance of semiconductor devices for providing this technology cannot be understated: they are used in almost all technology-based products, as well as household items.

And we are a net importer of other microchip-dependent ICT services, and computer, electronic, and optical products vital for logistics, communications and defence. In 2018, net imports of ICT services into Australia totalled $4.4 billion US dollars – up from $2.9 billion in 2008 – and the trade balance in computer, electronic and optical industry was $23 billion US dollars in 2019.

Like the rest of the world, Australia relies on Taiwan, South Korea, and China for the fabrication of semiconductors essential for the manufacture of complex and highly classified military capabilities.

The US had 37 per cent of the global semiconductor industry in 1990, but its dominance has been eroded by North Asian markets over the past three decades.

In 2020, Taiwan (22 per cent), South Korea (21 per cent), Japan (15 per cent) and China (15 per cent) accounted for 73 per cent of global semiconductor manufacturing, compared with the US’s 12 per cent.

By some calculations, Taiwan manufactures 60 per cent of all the world’s semiconductors and 90 per cent of the most advanced chips.

Each of these source countries are located at the epicentre of strategic hotspots in Taiwan and the Korean peninsula and may be the first to be excised from global markets in a military conflict, immediately throwing global microchip supply chains into disarray. It would be prudent for us to diversify away from North Asia and rely more upon the EU, India and the US for chip supply now, to ensure against an unpredictable future.

Other solutions are hiding in plain sight. A plan for sovereign control of our nation’s most vital needs must start at the top.

The Australian Sovereign Capability Alliance has put the case to Senate References Committee Inquiries into both manufacturing and naval shipbuilding that government should appoint a senior minister for sovereign capability, supported by a dedicated agency to determine and implement a plan of action, and that a separate agency under a different minister be tasked with independently reporting performance.

We believe that cabinet should form a dedicated committee for sovereign capability, chaired by the minister for sovereign capability, which brings together all relevant portfolios. Every minister and agency will have microchip dependencies. This is a whole-of-government challenge.

The next step is to measure the problem: only then can it be fixed.

In contrast to Australia’s piecemeal approach, the Biden administration on coming to office ordered a comprehensive top-down 100-day review (Executive Order 14017) of supply chain resilience, capability and stability in semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging, high-capacity batteries including electric vehicle batteries, critical minerals and other strategic materials, pharmaceuticals, and pharmaceutical ingredients.

An outcome, announced in August 2022, was a US government response to China’s ‘Made in China 2025’ plan through a major commitment to America’s semiconductor manufacturing sector, with US$50 billion in funding under the CHIPS and Science Act.

Bolstered by this move, memory chip manufacturer Micron committed a US$40 billion investment with the potential to create 40,000 new jobs in construction and manufacturing.

The Australian government should include microchip security in a President Biden-style, 100-day top-down review of Australia’s sectoral supply chain resilience, underpinned by the nomination of key operational capabilities for independent sovereign control and ownership. There is no time to waste.

Government must then act on the information exposed in the supply chain review by leveraging its purchasing power to empower Australian industry.

Microchip gaps, particularly in low-value, high-volume chips, might be plugged by extensive warehousing and storage of large volumes of imported chips under Australian government control, sufficient to see us through any extended crisis.

The more complex, high value-add microchips may need to be manufactured at home, by incrementally developing local production capabilities in areas of underdevelopment and by creating local deal flow by mandating sovereign supply and capability into government contracts.

Government must go further by ensuring ex-ante, strong contractual provisions with overseas-based manufacturing primes bidding for Australian work and local sub-primes to strengthen design, systems integration and ‘system of systems’ integration, microchip content, other critical technologies to extend production capabilities and Australian value chain participation over time.

Canberra, through the AUKUS alignment with Washington and Westminster, has obtained a competitive advantage.

US controls targeting China and other semiconductor players not aligned with US interests apply to 3D NAND chips of 128 layers or more, which are fabricated through a high-precision process with more than 1,000 consecutive processing steps that require the continuous operation of a set of semiconductor processing workhorses.

The non-volatile memory industry was upturned this year with the announcement, first by Micron, of a revolutionary 232-layer 3D NAND memory chip and then by SK Hynix of a 238-layer 4D NAND memory chip.

These advanced chip technologies and those which follow will go into our nuclear submarines, our F35 fighter jets and a host of cutting edge C4ISR capabilities.

We should use our defence relationships to partner with the US, lead chip manufacturers and the ‘Five Eyes’ supply chain to produce microchips at the cutting edge of high-value, low-volume manufacture. The broader economic benefits to Australian research and advanced manufacturing are clear.

There is money available for action. The government should reset its industry policy around ensuring Australia can make the high-end manufactures it needs to survive in a crisis, be it a war, a pandemic or a natural or economic disaster, without dependence on foreign governments.

Federal Labor’s promised $15 billion ‘National Reconstruction Fund”, the $800m Australian Research Council Grants programme, the multi-billion-dollar Defence acquisitions budget and whatever additional resources can be harnessed, need to be in part directed towards ensuring Australia’s essential microchip requirements are under sovereign control.

Australia already has an important R&D base upon which it can build new capabilities within the Defence Science and Technology (DST) Group, the CSIRO, and in the form of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) network under the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Scheme, which with a modest investment could become more commercially relevant and attract and anchor real commercial foundries.

We need to ensure that a local talent and innovation pipeline reinforces Australian-based commercial foundries by working with Australian universities and government R&D agencies, and via semiconductor-oriented degree and technical qualifications from universities and technical colleges. We should work with other trusted nations to strengthen this talent pipeline through coordinated research and training among key research universities.

The lead in all of this could be the defence industry if we are courageous and self-confident enough as a country, to put an end to the ‘off the shelf’ import culture of defence procurement.

We have the science and research excellence and the industry base and workforce, to better partner with allies and Primes to co-design, manufacture and build our own ships, submarines, aircraft and other defence capabilities, including microchips.

What’s missing is national determination and leadership.

Hon Martin Hamilton-Smith is a former SA Government Minister for Trade, Investment, Defence Space and Health Industries and Innovation, and is Director of the Australian Sovereign Capability Alliance (ASCA) www.australiansovereigncapability.com.au

Subscribe to @AuMa

Topics Analysis and Commentary Defence

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos