Carbon fibre composites – reuse, repair or recycle?

Fibre-strengthened materials are not easy to recycle, but should this even be the goal? Brent Balinski spoke to Dr Anastassija (Stacey) Konash from Swinburne University's Factory of the Future.

The cost and time taken to produce a carbon fibre-reinforced part has fallen in recent years. Due to the strength, weight, flexibility, chemical resistance and other benefits of composite polymers, they have found their way into more and more applications, from wheels to sports goods to airplanes and beyond.

Carbon fibre has been spruiked as a way to lightweight vehicles and therefore reduce emissions, and its physical properties have seen it widely deployed in wind energy generation.

Its sustainability credentials have been questioned, though. Besides the enormous amount of heat (and therefore energy) needed to turn precursor material into fibres and then to cure parts in an autoclave, carbon fibre products are difficult to recycle.

Like with tyres, for example, composites have been engineered for durability, and this has led to issues now that recycling is gaining in popularity.

The challenge for composites is, as waste management giant Veolia points out, “a technical one – the problem being how to separate the carbon fiber from the polymer resin that surrounds it without damaging and so losing its technical properties. Because in most cases, even if the polymer resin has reached the end of its life, the carbon fiber is still largely usable.”

Dr Stacey Konash, senior manager at Swinburne University’s Factory of the Future, believes the durability of the material should be exploited. The difficulty of doing so aside, recycling represents a waste.

“People are not thinking about repairs as a valid way of participating in sustainability. They feel the secondhand market is inferior. And that's one of the main reasons why the circular economy sort of struggles, I think,” she tells @AuManufacturing, adding that reuse and repair represent approaches that conserve more value.

“For example, I’ve spoken to several people who use carbon fibre bikes and I said, ‘you know, they can be repaired. And they're like, ‘but I don't know if I will trust [the bike] afterwards.’ I [ask] ‘but then how do you fly on the airplanes? Because they get repaired all the time.’”

Repair will create new issues, including responsibility for the performance of the product, but it is under-examined in the circular economy discussion, believes Konash, who earned a Fulbright Coral Sea Professional Scholarship earlier this year to investigate Industry 4.0 tools enabling circular economy efforts in the US. Her hosts will be the University of Buffalo and Rochester Institute of Technology’s Golisano Institute for Sustainability.

Konash will study the approaches to collaboration with US manufacturers, how they assisted change, and what can be adopted back in Australia.

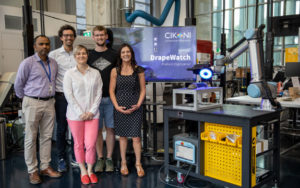

Engineer Jimmy Thomas, CIKONI Founder Jan-Philipp Fuhr, Senior Manager Stacey Konash, PhD candidate Benedikt Lux and Professor Bronwyn Fox at Swinburne's Factory of the Future (picture: Swinburne)

The struggle of making newer concepts – be they digitalisation or closing the loop on resources – relevant for businesses is a familiar one for Konash, who earned a PhD in electrochemistry at University of Limerick, worked internationally as a researcher, and spent nearly a decade in manufacturing firms in Australia. This included seven years at Universal Biosensors, finishing as Project Leader/Product development manager, followed by a role at a small firm involved in cosmetics and packaging.

“I thought, ‘okay, this is a small company, I'm going to implement all this knowledge about digitalisation and we're going to bring them to the front and they will get the best!’” she recalls, adding that company cultures and expectations proved a barrier to change.

“It didn't quite go according to plan.”

Other work at Swinburne to make fibre-reinforced composites more circular economy-friendly involves investigating non-thermoset/epoxy resins, which currently go into 90 per cent of carbon fibre products. This means that pyrolysis is the current dominant approach to recycling, with the material heated in a low-oxygen environment and the fibres reclaimed to be reused.

“We are working with some startups that have their specific resin that was designed to be reused. So instead of… pyrolysing it and burning it off, you can dissolve it in the solution of the monomer of that resin and reuse the whole thing again,” explains Konash.

“So it's truly reusable, because you don't have to dissolve it in a solvent and then extract it. … We're going to look into that to see how it's actually happening in our conditions and how many times can you do that before you establish enough degradation so that it's not going to make sense anymore.”

Featured picture: Reinforced Plastics

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos