Forging a way into the nuclear power industry

By Brent Balinski

Australia will eventually have eight nuclear submarines, delivered in partnership with either the US or UK, and a new base for them at one of three short-listed sites on the east coast.

A political embrace of civil nuclear power will come later, if it ever does. This is no barrier to a conversation on where industrial opportunities in this sector might exist.

Last week Dr Edward Obbard, head of nuclear engineering at University of NSW, went through on some of the possibilities, during a “mad dash” presentation on the evolution of nuclear reactors since the 1950s at a meeting of the Nuclear Skills Forum.

“The curious thing about a nuclear power plant is that most if it’s not nuclear. This secondary side is really what you see in every other thermal power plant,” he told an audience at Eilbeck Heavy Machining at Ingleburn.

“So all of the skills and the technologies and the standards and the industry that supports it are exactly the same as thermal generation, only they’re operating on a nuclear site.”

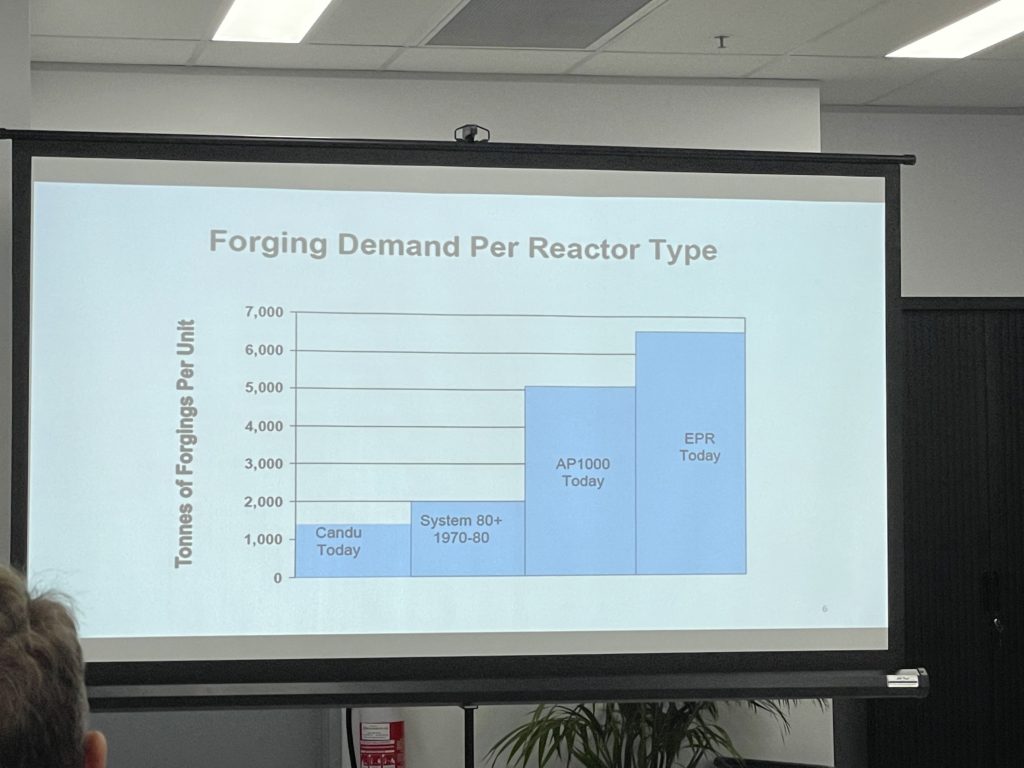

Reactors in any era so far have required a large volume of forged parts, and this has gone up with increased size, number of coolant loops in a reactor tank, and complexity of systems.

Reactors in any era so far have required a large volume of forged parts, and this has gone up with increased size, number of coolant loops in a reactor tank, and complexity of systems.

Forged parts are made of low-alloy steels. Designers have used progressively larger parts and less welding, which is generally submerged arc welding. The low-alloy steel filler is a weak spot, and made brittle over time by neutron radiation and requiring regular inspections of its integrity.

One major innovation was in Combustion Engineering’s System 80+, which used fully round forged rings in its pressure vessel, eliminating axial welds.

“The bigger you can make the forgings the better,” explained Obbard.

“You reduce the number of circumferential welds and you can even eliminate some of the longitudinal ones.”

As for future generations of reactors, powder metallurgy combined with hot isostatic pressing (PM-HIP) has been the subject of R&D in recent years by organisations including Electric Power Research Institute, the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, and Rolls Royce. This sees metal powder put in metal canisters, consolidated under heat and pressure into a near-net shape, removed from the canister, then machined.

This is combined with electron beam welding, which doesn’t need filler metal and therefore doesn’t create the same weak spots.

“A good electron beam weld after it’s been heat treated has exactly the same properties to the parent metal,” said Obbard, adding that the “huge challenge” remained of qualifying such powder metallurgy-produced pressure vessels to meet regulatory standards.

So where do the unmet needs exist?

According to Obbard, very large forgings – which also require a lot of work at the machining step after being pressed – are where.

The small modular reactor (SMR) industry, if it is to take off, presents another place where forging capacity will have to be beefed up globally, and “it’s not going to happen if we rely on the amount of forging presses that we have now.”

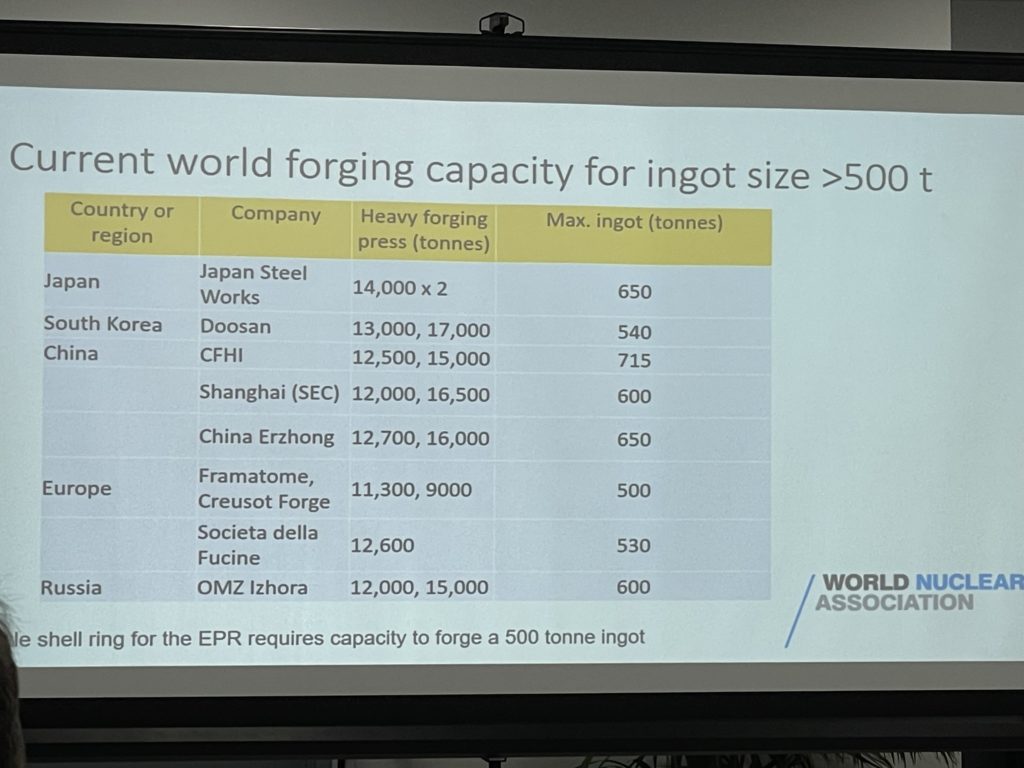

There are some forging sites in Australia, though maybe not operating at a size where they could currently participate. (See figures on forging capacity from the World Nuclear Association. WNA explains that “the nozzle shell ring for the EPR [a current reactor family] requires capacity to forge a 500 tonne ingot”. )

There are some forging sites in Australia, though maybe not operating at a size where they could currently participate. (See figures on forging capacity from the World Nuclear Association. WNA explains that “the nozzle shell ring for the EPR [a current reactor family] requires capacity to forge a 500 tonne ingot”. )

IBISWorld values the iron and steel forging sector in Australia at $727 million, and the largest three operators on their list are makers of rail fasteners, grinding media, and rigging components.

The demand for nuclear power could increase as countries move towards decarbonisation goals. According to modelling by the IPCC of scenarios that would limit global warming to 1.5 degree above pre-industrial levels, nuclear power would need to double its contribution by 2050.

“Forging is really the bottleneck for producing reactors at the moment. Well, apart from funding and social acceptance and all those other things,” said Obbard, with the audience sharing a sympathetic laugh at the comment.

“Because there’s such a restricted supply chain of large forgings, it’s the kind of thing that would be relevant in Australia for export. Because if the nuclear industry is growing internationally, there’s obviously a shortage of these parts.”

Picture: Sheffield Forgemasters in the UK (Sky News)

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos