Slag, sustainability and steel

Metal manufacturers around the world are trying to lessen their greenhouse gas output. Brent Balinski spoke to the CSIRO’s Dr Mark Cooksey about some of his organisation’s work regarding green steelmaking, and why he believes the de-carbonisation trend is an opportunity for Australian metal producers.

Every time there is news on Australian trade figures, we get a reminder of the importance of steel. Our top export – iron ore – has played an important role in the country’s wealth, and has found an eager customer in fast-developing China.

Steel is the most widely-used metal on earth, and currently irreplaceable. Bridges, buildings, vehicles, and innumerable other items in our world depend on its strength, versatility, and well-understood properties.

At the same time, the steel industry is undergoing major changes, particularly around the way it uses carbon. The production of a tonne of steel creates around two tonnes of carbon dioxide (using a blast furnace then oxygen furnace. Remelting scrap steel through an electric arc furnace produces around 0.5 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel.)

Picture: ABC News/Nick McLaren

Making metal creates almost a tenth of the world’s CO2 emissions, with these dominated by the iron and steel industry. This is contributed through the use of coke as a reducing agent, and electricity to produce heat.

Steelmakers are busy trying to lessen their impact.

Sanjeev Gupta’s Liberty Steel is investing heavily in renewable energy capacity. Australia’s other big steelmaker, Bluescope, aims to decrease the emissions intensity of its output by 1 per cent a year to 2030.

There will be transformative shifts within the industry in the coming years. The World Steel Association lists breakthrough technologies under development worldwide as using hydrogen as a reducing agent, carbon capture and storage, carbon capture and utilisation, biomass as a reducing agent, and electrolysis among these.

Dr Mark Cooksey, Senior Principal Research Leader at CSIRO, believes it’s a good thing for metal producers to be on the front foot with shrinking their carbon use. In future, extra challenges could come from a price on carbon, bank financing decisions, and maintaining social licence to operate. Change will be, Cooksey says, “a situation of not if, but when”.

“Steelmaking is about six per cent of the world’s CO2, and most of that is because it consumes coal directly in the process,” he tells @AuManufacturing.

“If you’ve got a coal power station, there are alternatives such as solar power or wind power. For steel making, though, you can’t just simply say, ‘We won’t use carbon or we won’t use coal.’ You need a reducing agent.”

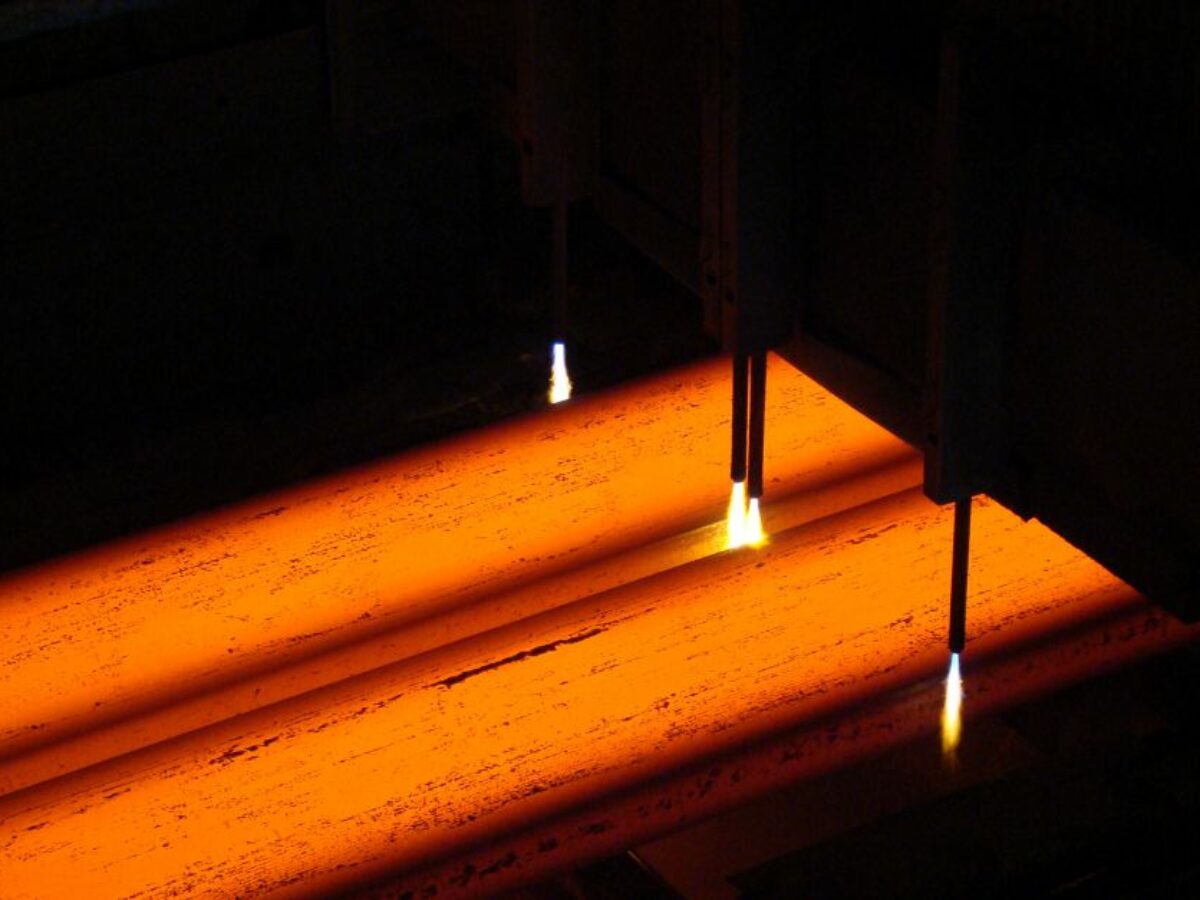

Self-sustaining pyrolysis plant (picture: https://www.csiro.au/en/Research/MRF/Areas/Community-and-environment/Responsible-resource-development/Green-steelmaking)

For about a decade, Cooksey’s organisation has been developing a “self-sustaining pyrolysis” process, currently at pilot scale at its Clayton site and able to produce 100 kilograms per hour of charcoal from biomass. The reactor is being optimised and industrial partners are being sought to take the work further.

“The advantage of using charcoal from biomass is that if you do it right, when that biomass is grown it’s absorbed a lot of CO2 out of the atmosphere,” explains Cooksey.

“Then you consume the charcoal and you produce CO2 again, but the net amount of CO2 you’ve produced is a lot lower than if you had used coal.”

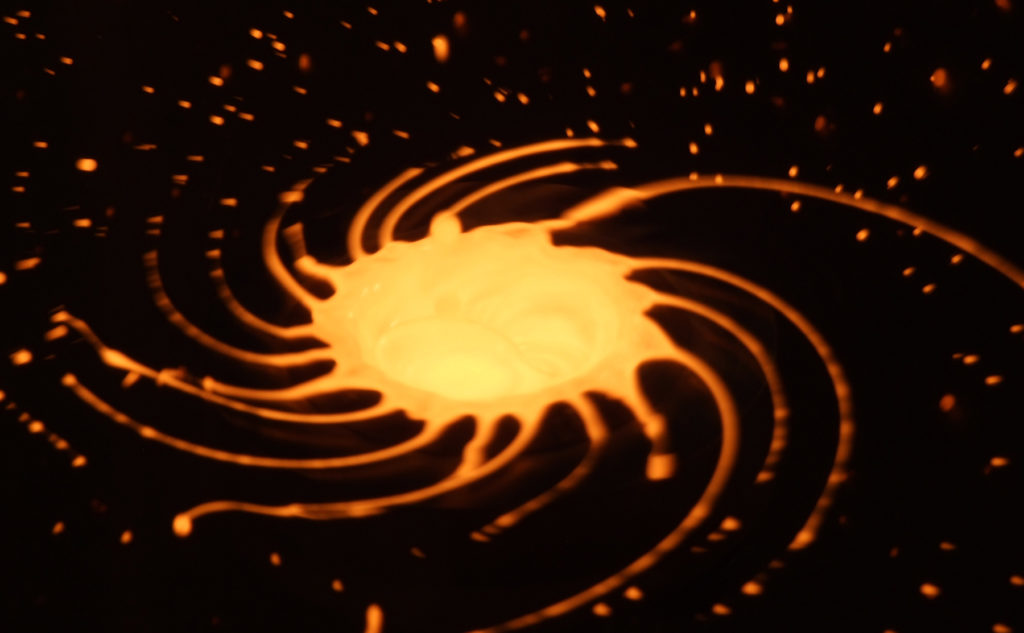

Another technology that has the potential to make steelmaking greener is “dry slag granulation”, which has been under development at CSIRO since 2002. DSG takes molten blast furnace slag and atomises it under centrifugal forces with a spinning disc, creating glassy granules that can substitute for Portland cement.

This saves on the emissions created by making heat for calcining limestone in regular cement manufacture, and recaptures energy from the blast furnace to be used as process heat at the steel plant. It also saves on the large amounts of water used in wet granulation.

According to CSIRO, full adoption of DSG could save 60 million tonnes of greenhouse gas from being produced.

In 2015, DSG was licensed to China’s MCCE, and a demonstration plant, able to produce 300 kilograms of granulated slag per minute, came online earlier this year. China creates about six-tenths of the blast furnace slag in the world, and adoption could have a major impact, says Cooksey.

“History shows that it takes a decade or two to go from an idea to a commercial product in the metal production industry; on dry slag granulation, we’re much closer to the end of it than we are to the start,” he says.

“The day that the demonstration plant first performed well was one of the most satisfying of my career, because it’s really difficult to develop a new process and commercialise it.”

Other highly-promising efforts to make greener metal are underway globally. This website has reported on the Bill Gates-backed MIT spinout Boston Metal, which is commercialising a zero-carbon molten oxide electrolysis method, and the SSAB, LKAB and Vattenfall consortium’s HYBRIT, which uses hydrogen instead of coking coal as a reductant.

Molten steel (Picture https://www.csiro.au/en/Research/MRF/Areas/Community-and-environment/Responsible-resource-development/Dry-slag-granulation)

The path to commercialising any novel process is generally long and painful, but taking the carbon out of metal manufacture offers great hope for Australia, believes Cooksey. He cites a presentation by University of Melbourne Professor Ross Garnaut, where the economist makes a case for steel production returning from nations including Japan and South Korea.

Renewable energy (e.g. shipping green hydrogen or transmitting electricity) is more expensive to transport than fossil fuels, so cheap, abundant generation in Australia would be especially advantageous for energy-intensive businesses, believes Cooksey.

For decades Australia made strategic efforts to grow its metal production, capitalising on what was once cheap fossil fuel energy and what was (and still is) an abundance of ore to value-add.

“That started to change in the early ’90s as power prices went up and concern about sustainability grew. The fact that the cost of renewal energy looks like coming down quite a lot and Australia has huge renewable resources means that it’s conceivable for Australia to actually aim to be a globally significant metal producer,” Cooksey asserts.

“We’ve got the ore, we’ve got good renewable energy resources, and we’ve got the intellectual capacity. I think our starting point should be aiming big: let’s become a leading global producer of green metal and work back from that. Rather than saying, ‘Oh well, other countries do it, so we can’t do it.’ We actually can and we should try.”

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos