Slowly getting closer to the pointy end

Last week Brisbane medtech company Vaxxas, which is trying to reinvent the needle, announced plans to move to industrial-scale production. Brent Balinski spoke to the company's Dr Angus Forster about getting from invention to impact.

Back in 2004 a brilliant Australian rocket engineer-turned-medtech inventor doodled an idea on a notepad.

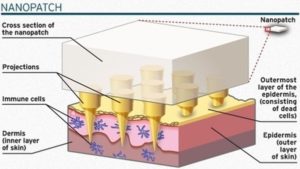

Mark Kendall, then a lecturer at University of Oxford, was interested in the high number of immune cells in the skin. His concept was a patch with thousands of tiny needles – delivering vaccine between skin layers rather than into muscles – where the dose might be more effective as well as pain-free.

The inventor returned to the University of Queensland in 2006 and formed a team to develop the “nanopatch.” Vaxxas began in 2011 to commercialise the device, challenging the tried-and-true hypodermic syringe, which has been around since the mid-19th century. Aside from requiring less vaccine for the same effect, the invention also uses a dried coating on its projections, meaning no need for refrigeration in transport and storage.

According to The Australian Financial Review, Vaxxas has raised over $55 million so far in equity and over $40 million in non-dilutive funding since being formed.

The patch remains in development, though two major milestones were announced last week. Pharma behemoth Merck – a partner to Vaxxas since 2012 – announced it would invest $18 million for the use of the patch with an undisclosed vaccine.

Diagram of the vaccine delivery patch.

(Romar Engineering)

And production and packaging specialist Harro Hofliger had been commissioned to collaborate on industrialising patch-making, first through a pilot line next year and then targeted modular lines with capacity of five million units a week. Production is currently on a proof-of-concept rig.

“It's a great idea, and we know it works from an immunology perspective, but how do you scale that up from a manufacturing perspective? How do you make tens of millions of doses per annum and make them to the standards that you need for pharmaceutical vaccine product?” Dr Angus Forster, Chief Development and Operations Officer, tells @AuManufacturing of a broad question they’re trying to answer.

Getting the idea to customers is a serious challenge, he adds.

A needle and syringe isn’t anything people enjoy, necessarily, but it is well-understood, effective, and cheap. Pre-filled, each can be made for about one US dollar, excluding vaccine.

“If you [cost] any more than that, you've got to add a lot of value to the technology to be worthwhile progressing,” says Forster of what they're competing against.

There have been two broad categories of R&D challenges, roughly described as “can you make it and does it work?” They are volume/quality questions and medical validation ones.

“We very early identified what our key risks were to successful commercialisation and focussed on addressing those, while at the same time getting enough positive development data from clinical studies to show that this technology will work and will translate,” explains Forster.

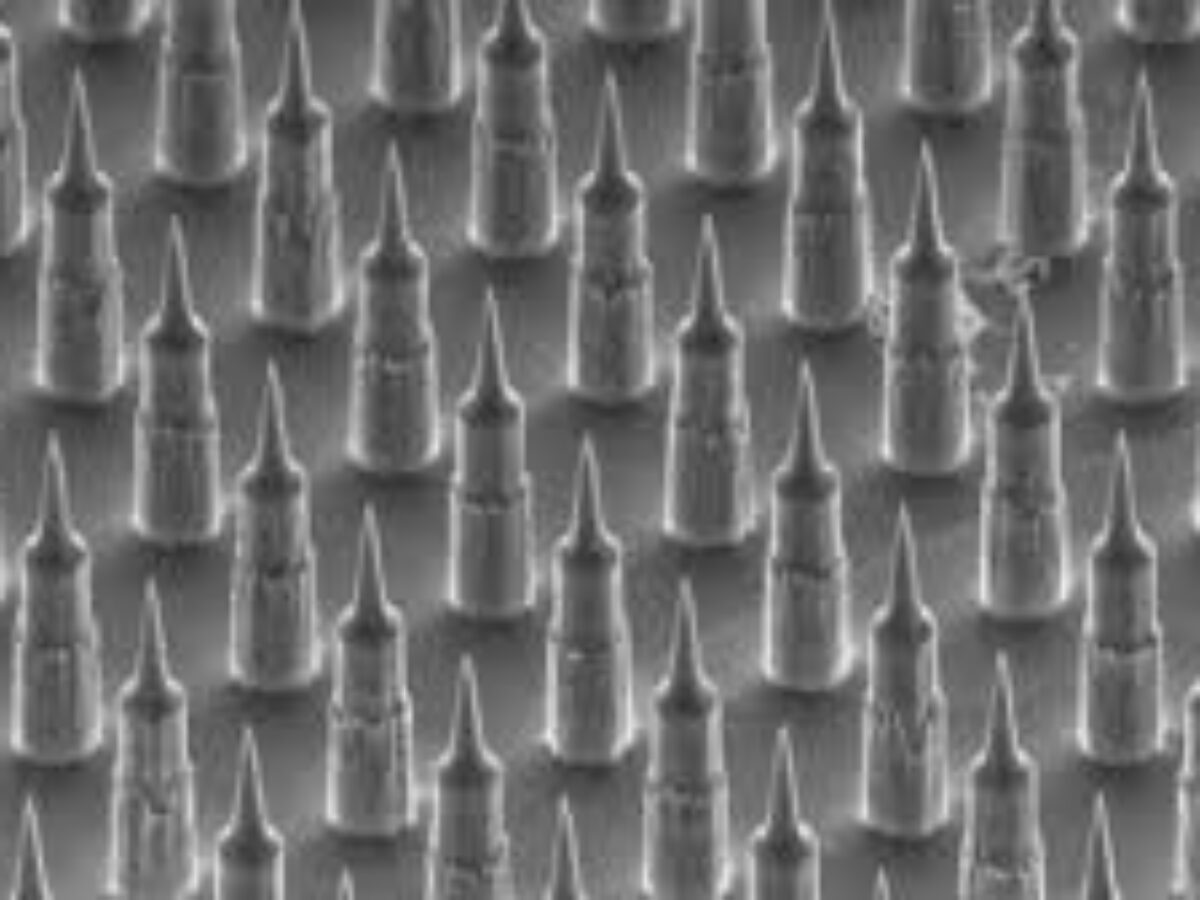

The patches were originally made of monocrystalline silicon, with features created through deep reactive ion etching — a material and a production technique familiar to the electronics industry. Nowadays they are micro-moulded out of medical polymer.

“We've really sort of tried to reinvent injection moulding in some regards,” says Forster.

The invention’s name has also changed to HD-MAP (high-density microarray patch) from Nanopatch. At the time of writing the company’s website has not yet included the rebrand, undergone to better describe the product: the thousands of needles on each 1 cm square are 250 micrometres long, rather than being at the nanoscale, and MAP has developed as a recognised category in medicine.

Vaxxas is based out of UQ’s Translational Research Institute. The current home for manufacture is okay for phase one clinical trials, but soon won’t be. Products for later-stage study need to be manufactured under a TGA license, meaning a move is on the cards, says Forster.

“we know it works from an immunology perspective, but how do you scale that up from a manufacturing perspective?” – Angus Forster

(Picture: nanomelbourne.com)

“One of our next set of challenges is where do we move the operations to, to enable that manufacture of clinical trial products to stay here in Brisbane,” he explains, adding that the team is aiming for 2022 or 2023 to be manufacturing using its final commercial-level process.

“For pharma, verification and commissioning can take one year to 18 months from the time you actually have the machine at site.”

“It’s a bit of a current challenge for us to think about where do we go next. There's not quite the facility available here in Brisbane that we can just jump into, because our requirements are very, very specific.”

As anybody involved in developing ambitious medical products knows, a large supply of patience is crucial. A commercially-produced vaccine delivered by HD-MAP might be five to seven years away — many years after the first doodles were committed to a notepad.

Does Forster, who has headed R&D at the company since 2012, have any advice for those who have a long wait ahead of them?

He suggests knowing the main barriers to successful commercialisation early on and addressing them rather than putting them off. “Can you make it and does it work?” are questions they’ve had to answer in tandem, and over years, developing considerable IP around new processes while proving that the spiky little squares worked on animals and then on humans.

“Then the other part was really focussed on how we then make this commercialisable and keeping that focus and not getting too distracted about all the other things that you can do in business,” Forster adds.

“You also have to celebrate your wins a little bit as well, because there's always something to do next. When you get a good result from a clinical study, you immediately think of, ‘well what's the next issue?’ Because there's always another issue. But you’ve got to also say ‘we've done a great job here. We've got good clinical data.’ Let's just enjoy that for a minute.”

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos