The terrible trickiness of growing an Australian semiconductor sector

What does Australia have in the way of a semiconductor industry, and why does that matter? Brent Balinski spoke to Professor James Rabeau, the lead author of a national study of the sector published at the end of last year.

As this title has written before, a semiconductor industry should be foundational for a nation aspiring to industrial sophistication.

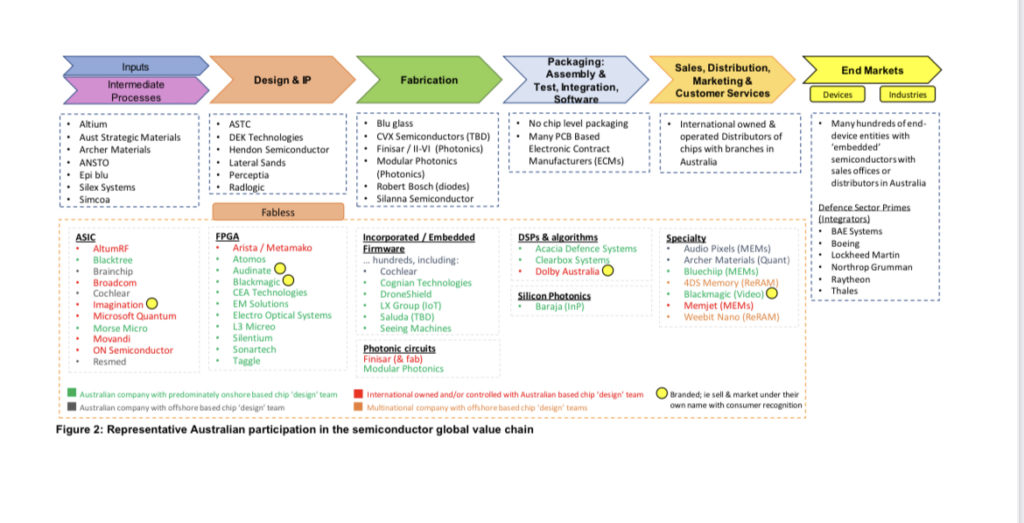

Chips of different kinds — for storing information, processing it, communicating it, and other functions — feature in just about any advanced product you could name. They are a “critical intermediate good in a vast value chain” — notes a recent report for the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer by University of Sydney Nano Institute — enabling other industries.

An individual semiconductor might contain 300 different inputs subject to maybe 50 types of processing and testing tools during manufacture.

This fantastically competitive industry invests over a tenth of overall revenues on R&D, with a hugely complicated, highly-globalised supply chain with countless highly-specialised niches.

As an Accenture research paper puts it: “the making of one semiconductor chip requires thousands and thousands of people, most of whom have specialized knowledge and specialized jobs, spanning myriad industries, countries, and regions.”

According to the Nano Institute study, led by Deputy Director Professor James Rabeau, a correlation exists between a country’s semiconductor industry participation and its economic complexity. Japan maintained a strong representation as well as top place in the EC stakes for two years compared, 1995 and 2018. As South Korea grew its share of the global semiconductor industry over those years, its complexity leapt also.

Australia is much more a consumer than producer and lags in value creation and capture. Its economic complexity ranking in 2018 was 87th overall. “This study was unable to uncover a major Australian company, whose core business activity is participation in the semiconductor design, development and production value chain,” the report notes elsewhere.

“The overriding sense from people is that actually right now is a different time and this is the right time, and the opportunity is right for us to make a play into the sector in a more meaningful way to establish something,” says James Rabeau.

(Picture: Linkedin)

You can’t just flip a switch

Strengthening the local sector is not simple, says Rabeau, who routinely qualifies potential answers with at least one associated difficulty.

To begin with, the Australian companies are small and scattered, with no significant volume of them creating a specific technology, and each “with different technological requirements for what they’re building,” he tells @AuManufacturing.

“It’s quite spread across, which makes that whole decision-making process about where you want to focus a manufacturing initiative on [more difficult.]”

Conversations on how to grow an industry often include a question about where to build a foundry. This is an obvious suggestion, but not always a good answer, he adds. As with any attempt to grow a nascent or non-existent sector, there are push and pull and other considerations. Plonk a billion-dollar factory down in Australia and it would lack the necessary supporting skills and suppliers to operate.

“One of the biggest things — this came up in a lot of the conversations — is the notion of the ecosystem, and that you can’t just flip a switch or even just buy in a facility and all of a sudden you’re good to go and and everything is running smoothly,” he adds.

“I’m at a university. I know that there is supply and demand in terms of what we offer… If we had a real vibrant silicon semiconductor industry, even if it wasn’t huge but was happening and growing, then I imagine more students would be interested in this space because they’d see jobs at the end of it. That stuff takes a long time.”

The importance of being prepared for the future is another reason to care. Australia has pockets of excellence — notably at University of Sydney and its sandstone rival University of NSW — in quantum computing.

Rabeau returned to academia (he is also co-founder of a quantum technology startup) after a year as Microsoft’s Principal Program Manager, Quantum Computing. He is therefore highly interested in the possibility of a burgeoning local quantum industry.

“The question that comes up is ‘Well, OK, what about in 15, 20 years if and when something like quantum really is pumping and there’s bigger, well-defined markets for it. Where are the things that are required to build quantum computers? Where are they going to be made?’” he asks.

“Are we going to actually miss the boat and everything is going to get offshored because we simply don’t have the underlying technologies and capability and skill sets to feed it?”

He adds that quantum computing is just one family of next-generation technology that might take off. Picking which will be successful is guesswork. Another difficulty. To that you could add stability of support across changes of government, a further major challenge.

Australia has a small number of fabricators, such as Silanna and BluGlass. (Australian Semiconductor Sector study, page 17.)

A staged approach

As far as where to invest public money with the aim of making the most of emerging semiconductor industry technologies, Rabeau suggests perhaps something geared towards startups prototyping or doing low-run production. There is currently nothing much in Australia between an R&D facility and, say, a foundry run by TSMC, the Taiwanese contract manufacturing giant. (According to reports last month, its upcoming Arizona facility will cost $US 35 billion.)

“People like myself who are developing things in a lab and want to maybe prototype a device and need a bit more production-scale equipment and skills and resources and so on, and even just to do that, I would have to go overseas to a place like Imec or other places that fill that role,” he says.

“Now even for that kind of thing, the scale of investment is quite large and even to get to that would take some real careful thinking about, ‘what is this facility going to do? What’s the risk associated with investing in this?’ …What we sort of recommend is a staged approach.”

Among recommendations in the report is a bureau service for fabless businesses, which design but do not produce, and which make up most of the Australian semiconductor companies. Such a broker would ideally mediate between these and reliable offshore producers, aggregate scale, create networks, and gather intelligence about where local investment is best made.

As for what parts of the semiconductor value chain in Australia are best placed to grow, this is too hard to pinpoint, says Rabeau, though he adds that there is potential in high-tech university spinouts.

It was hard to get a simple, all-encompassing answer among interviewees as to why the local industry hadn’t flourished. (The Australian Semiconductor Sector study received input from over 100 individuals, companies and government agencies.)

Some didn’t see an issue at all and knew they could just look overseas for fabrication. Some startups said the right skills were hard to find locally. Others cited a view that government programs had been tried before and didn’t amount to much.

Rabeau is hopeful the time is right for a focussed attempt to build Australian capability in an industry that drives the progress and prosperity of the modern world.

“The overriding sense from people is that actually right now is a different time and this is the right time, and the opportunity is right for us to make a play into the sector in a more meaningful way to establish something,” he offers.

“Maybe it’s because of the sovereign capability, manufacturing capability argument, security, maybe it’s because we’re now getting to a point where people are routinely running out of local talent coming into the pipeline that they’re like, ‘well, we need to do something about that.’ I think there’s a big technology argument as well, like I mentioned, about the next-generation technologies and the fact that we do have a lot of talent here and a lot of things that we can seize the opportunity in. And people want to make sure we capitalise on that.”

The full report can be read here.

Featured picture: www.anandtech.com

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Analysis and Commentary

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos