Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

What to make of all this plastic?

This week @AuManufacturing will feature a collection of Aussie innovators who are giving plastic a second life. But first, some context on the issue and why it matters. By Brent Balinski.

Plastic – that ubiquitous, incredibly useful, very broad set of materials – has gotten a lot of bad press lately.

Last week we heard that it had literally rained microplastics in Colorado, and that there were arctic ice floes sampled that contained weirdly high levels of — well, you can guess. It is raining and snowing plastic.

Back home, industry minister Karen Andrews announced $20 million in funding (pledged during the election campaign) through round 8 of CRC-P grants for “projects that address reducing plastic waste and [boost] plastics recycling.” It came a week after a COAG agreement to eventually set a timetable to ban waste exports, and to establish commitments to “reduce waste, especially plastics.”

David Hodge, managing director of award-winning plastic film recycler Plastic Forests, believes that an eventual ban on waste exports is fantastic news, but the difficulties, skills, and costs required to turn used plastic into products are being underestimated.

David Hodge (Picture: Herald Sun)

“People don't realise just how expensive the industry is,” he tells @AuManufacturing.

“The latest RPET – recycling PET plant – to come on board at an industrial scale in California was about 100 million dollars.”

Last week the Australian Council of Recycling (ACOR) told The Guardian that a zero waste export goal was welcome, but needed to be matched with “very big deeds and dollars.”

When it comes to plastic, there is a lot of work to be done. According to the National Waste Report 2018, “only about 12% of waste plastics are recycled” compared to 90 per cent of metals, 60 per cent of cardboard, and 27 per cent of our hazardous waste. Another report crunching 2016-17 figures found that for the small amount of Australian plastic that was recycled, this mostly happened overseas.

The options to export are shrinking. Following China’s National Sword policy, which effectively banned imports of plastic and other forms of solid waste, other nations in the region have started knocking back our recyclables.

The Chinese ban in early 2018 has left other countries with options including landfill, burning, using a shrinking number of importers, or developing their own recycling capacity. Since 1992, China had imported almost half of the world’s plastic scrap. One estimate is that, by 2030, “111 million metric tons of plastic waste will be displaced” due to National Sword.

.

Mark Yates, founder of Replas – which turns second-hand plastics into products including outdoor furniture and bollards – tells @AuManufacturing, “The whole world has the same problem, and the whole world is waking up.”

As an example, he cites machinery he ordered nine months ago that is still two months away from arriving.

Must have pull

Gayle Sloan has been CEO of the Waste Management and Resource Recovery Association of Australia for three years. In that time she says that her industry has become part of the national psyche, a focus on minimising waste creation has sharpened, and people are beginning to appreciate that the need for market pull to develop a recycling industry.

“We've got an understanding about markets and the need for markets for recycled materials in order to make industries globally successful, because what we're trying to do is manage resources well,” she tells us.

Some, like the ACOR, believe that recycling infrastructure will need big investments. The country’s 193 material recovery facilities “are nowhere near sufficient to sort Australia’s annual recycling,” observed one expert last week. The crisis in Victoria after SKM’s collapse is well-documented.

The problem is a multi-faceted one, but everyone asked about a way forward for this article highlighted the importance of developing market pull, for example through infrastructure procurement.

Materials engineer Professor Veena Sahajwalla, Founding director at University of NSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) and director of the NSW Circular Economy Innovation Network, says “you've got to let the market take its course.”

“You set up any infrastructure, set up a facility, if you know that the market is there and can sustain the cost of installation of the infrastructure.”

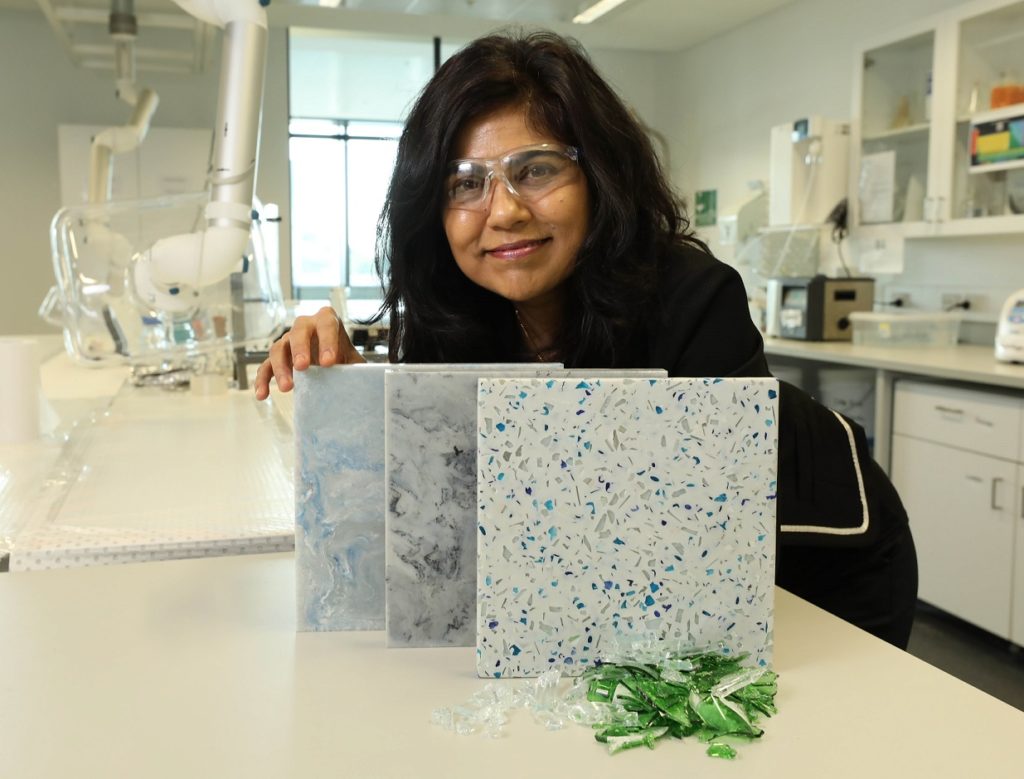

Veena Sahajwalla (picture: Grant Turner, Mediakoo.com)

Sahajwalla’s work includes an internationally-successful “green steel,” which uses tyres and plastic in steelmaking, and reclaiming plastic from e-waste and toys to make 3D printing filaments. Current projects include pushing the limits for how many times a plastic feedstock can be reused by modifying processes and additives.

As Sahajwalla does, Professor Damien Giurco of UTS’s Institute for Sustainable Futures points out that quality is an important and sometimes overlooked part of the circular economy conversation.

“We would want all the quality and safety and standards and specs that are front of mind for virgin materials,” he tells @AuManufacturing.

Walk and chew gum

Citing Japan, a leader in plastics recycling, Giurco says that the range of beverage containers on offer could be streamlined by companies, and this would be one way to make reuse easier. Do we really need so many different types of kombucha bottle?

“I think it's good to be doing thinking at the systems level… Maybe [just] have clear plastic, and then you don't need to set up for recycling green plastic,” he offers.

With disappearing options for exporting waste and a move to create and use plastics more responsibly, design for recycling can only become more important.

Yes, market demand deserves a lot of emphasis, says Sloan, but we will need to walk and chew gum when it comes to solutions.

“I don't think there's been enough emphasis on that redesign piece,” she believes.

“We need to start redesigning now for the future. So with redesigning for reuse and recovery and recycling… If it's still being designed and brought into the community, what happens when it's there?

“We actually need to as much, put emphasis on design to go circular, as opposed to dealing with demand once it's in circulation.”

Major challenges tend to need a range of responses. Procurement changes are one, and we are likely to hear more on this the next time the country’s environment ministers meet.

Who are the real recyclers?

War on Waste's Craig Reucassel and Mark Yates of Replas (picture: www.replas.com.au)

There are opportunities for manufacturers, and this week we will be featuring several who are trying to grab them. They are each offering a very different, very clever response to the plastic problem.

One of them, Replas, has been at it since 1992. Founder Mark Yates says that the power to make a difference lies with purchasers, and this needs to be recognised. No market? No solution.

“The trucks that run around and pick up the recyclables kerbside, they say they're the recyclers, the MRFs say they’re the recyclers, the traders say they're the recyclers, and even the manufacturers say they're the recyclers,” he tells us.

“The true recyclers are the people who purchase recycled products. The emphasis has been in all the wrong area – the traders are just that – traders, the MRFs are logistics, the trucking companies are logistics.

“You do get washed out in the green, there's a lot of greenwashing with who the actual recyclers are, I don't even believe we’re the recyclers, we happen to use recycled polymers as our feedstock but the true recyclers – the people who purchase – don't get the mention that they should.”

Featured picture: Shutterstock/Alaettin YILDIRIM

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos