Monash spinout believes it has core ingredient for electric aviation revolution

Kite Magnetics recently completed an $1.85 million seed round and hopes to be the Rolls-Royce of e-aviation. Brent Balinski spoke to co-founder Dr Richard Parsons.

Occasionally you have a conversation that reminds you that things are an awful lot better than they used to be.

For me I had such a conversation a few weeks ago, with a young researcher-turned-entrepreneur who co-founded a company in May to commercialise his scientific breakthrough.

Until recently Dr Richard Parsons considered a lab at Monash University his “happy place”. The materials engineer – from a family of engineers – had a focus researching magnetic materials, earning a PhD under Deputy Head of Materials Science and Engineering at Monash, Professor Kiyonori Suzuki.

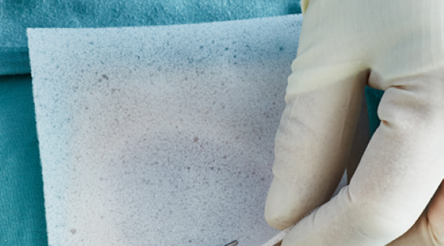

Parsons and Suzuki spun their breakthrough work in nanocrystalline magnetic core materials – named Aeroperm – out into a company named Kite Magnetics, which hopes to develop the world’s highest-performing electric motors, initially for aircraft.

At the beginning of October, Kite announced $1.85 million in seed funding, with investors including Investible Climate Tech Fund, Galileo Ventures, and Breakthrough Victoria.

“The idea is that with our tech, electric aircraft can fly further and carry more,” Parsons told @AuManufacturing.

“[Those are] currently… two of the biggest limitations for the adoption of electric aircraft.”

The elaborate process to make their key invention, which is mostly iron and which Parsons describes as resembling kitchen foil, leaves a material with “ten times lower energy loss” compared to existing core alloys, due to “quantum mechanical effects.”

Kite sees potential to create electric motors for everything from hypercars to vacuums, but believes the biggest need is in electrified aviation, which is generally agreed to be a long, long way from providing long haul flights due to low battery energy density.

“It’s definitely not because it’s the easiest industry to get into,” said Parsons.

Picture credit: Kite Magnetics

He aims to get to market by offering electric propulsion solutions for retrofits, initially making motors, then inverters and potentially components associated with propeller control.

Asked why he’s chosen to enter the e-aviation value chain by making motors rather than maybe licencing Aeroperm, Parsons says that it was the only approach that made sense.

“They could see the benefits, but not a clear path to market Kite Magnetics could see,” he says of motor companies approached.

A background in electric motor design as well as materials development told him that a new, unfamiliar material would take time to be accepted, and there was no point in waiting.

“It’s a bit like the discovery of carbon fibre. If you’re building aircraft out of aluminium for 50 years and someone comes along with a big roll of carbon fibre, that’s great, but what can you do with it?” he shared.

“For me, personally, I could see that if this technology was going to get out of the lab and have a real impact on the world and make a difference in aviation, that was going to have to be driven by myself.”

Putting aside the evaporation of easy finance this year, it is arguably a much better time for an Australian researcher to try and commercialise their breakthrough than ever before.

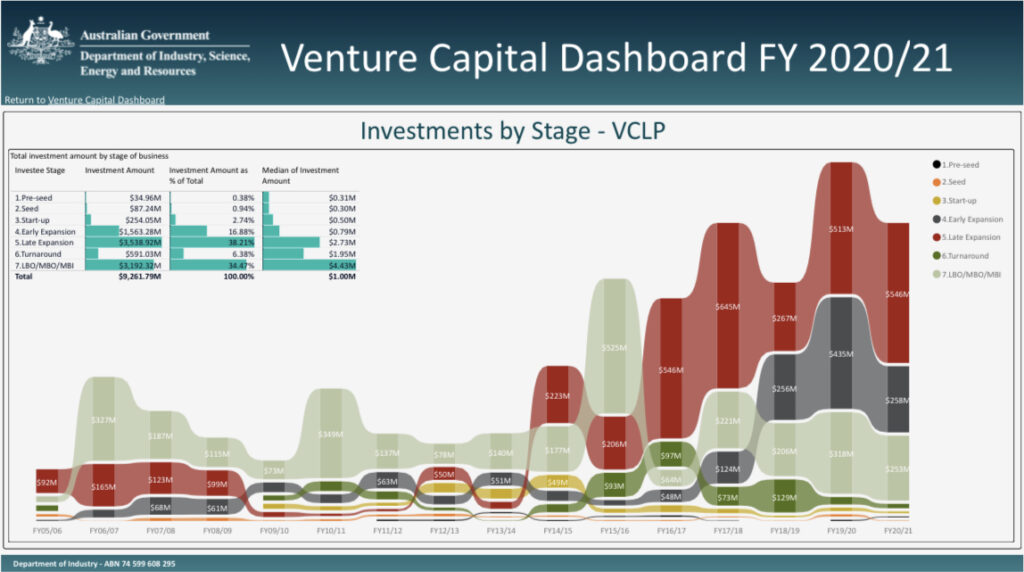

Last year ANZ startups raised over $10 billion, more than double 2020’s figure (itself a record.) This would have been unthinkable in a pre-”Ideas Boom” age. The department of industry’s Venture Capital Dashboard figures (see below) show a welcome trend.

Source: https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-02/venture-capital-dashboard.pdf

Technology entrepreneurs – whether at universities or not – no longer have to head on a plane to San Francisco as the default option.

Consider these comments from 2015 by Ivor Reis, a former Morgans Senior Analyst and Australian Financial Review scribe.

“A young Australian today with a world-beating new technology or a paradigm-shifting new business process has more chance of being struck by lightning than they do of being able to raise less than $1 million in venture capital,” wrote Reis.

“The smartest of our next generation of technology entrepreneurs learn this quickly, which is why they head to the United States by their hundreds each year.”

When we spoke, Kite had just hired its first non-founder engineer, and was preparing to start assembling “a world class electric motor test facility” at Clayton, to be used to test the company’s first-generation 65-kilowatt electric motors.

Parsons is unsure that he would’ve been able to take his leap of faith even 18 months ago, and believes appreciation of the importance of “deep tech” has vastly improved of late. There’s a better shot at making in Australia what’s invented here.

“We’ve got access to a fantastic pool of talent here in Australia,” believes Parsons. (Picture credit: Linkedin)

He mentioned MagniX, a pioneering electric propulsion business born on the Gold Coast in 2009, acquired by The Clermont Group in 2014, headquartered in the US since 2018, and which finally shut its Australian R&D operation during the first wave of the pandemic.

“We’re very, very committed to making sure this is an Australian technology that stays and is developed and pursued here,” added Parsons.

There is no question that commercilising high-tech hardware in Australia is difficult, but this title has noticed an increasing number of young founders setting out with both clever ideas and the sort of optimism that can’t not rub off on you.

Though this article has quoted liberally from the Kite co-founder, it will close with an extended example of the above.

“There is no doubt that access to capital is a little bit more expensive in Australia… At the same time, [there’s a] huge push from state and federal Government right now to support what we’re doing,” said Parsons.

“And to be honest, with the shutting down of the car industry, we’ve got access to a fantastic pool of talent here in Australia: world-class engineers, the best of the best. There’s no reason we can’t do these things here. And there’s a good reasons why companies like Bosch have engineering facilities here and not elsewhere, because we do things really, really well.

“And so when it comes to trying to build, essentially, the Rolls-Royce jet engine manufacturer equivalent right here in Australia. There’s no reason we couldn’t have a factory in Dandenong: a big warehouse, polished floors, engineers in gloves, carefully assembling multi-megawatt, world-class propulsion systems for aircraft. That’s something we could do really well.”

Main picture credit: Kite Magnetics

Further reading

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards Defence Manufacturing News Podcast Technology Videos