Recycling: the great green opportunity?

According to a recent PwC report, the circular economy offers a potential $1.86 trillion nationally in new economic value over the next decade. Brent Balinski speaks to a few experts about the opportunities attached to recycling and the circular economy.

In a few years, recycling and the circular economy have gone from peripheral to undeniable issues in manufacturing.

The federal government’s ten-year roadmap for Recycling and Clean Energy — one of only six National Manufacturing Priority sectors it currently deems worthy of focus — is expected out within weeks. As one of the six areas of “comparative advantage and strategic importance” it will share in a budgeted $1.3 billion in federal grant money, as well as other grants.

The issue

Recycling capacity shot up in importance with China’s waste import ban in 2018. This year Australian exports of glass were banned in January, to be followed by whole tyres in December, with a total waste ban eventually in effect in July 2024.

We don’t have enough capacity to handle the necessary recycling. But the export bans – while welcome – only scratch the surface of Australia’s circular economy opportunity, Lisa McLean, CEO of NSW Circular, tells @AuManufacturing.

“Australia generated over 75 million tonnes of waste in 2018-19. Only 6 per cent of this was exported. The four materials on the export ban list — glass, plastics, tyres, and paper and cardboard — represented a third of the total 4 million tonnes of waste exported that year,” she says.

“This alone has ignited momentum for substantial new investment in Australian recycling infrastructure. Looking beyond our exported waste, there is an even more significant onshore opportunity for materials recovery and emissions reduction that is five times the size of the waste export market: the 20 million tonnes of materials that go to landfill every year in Australia.”

“the core idea of the circular economy is around keeping materials in use for as long as possible in their most high-value form before recycling and reinvention into new products,” – Lisa McLean, NSW Circular (picture: www.nswcircular.org)

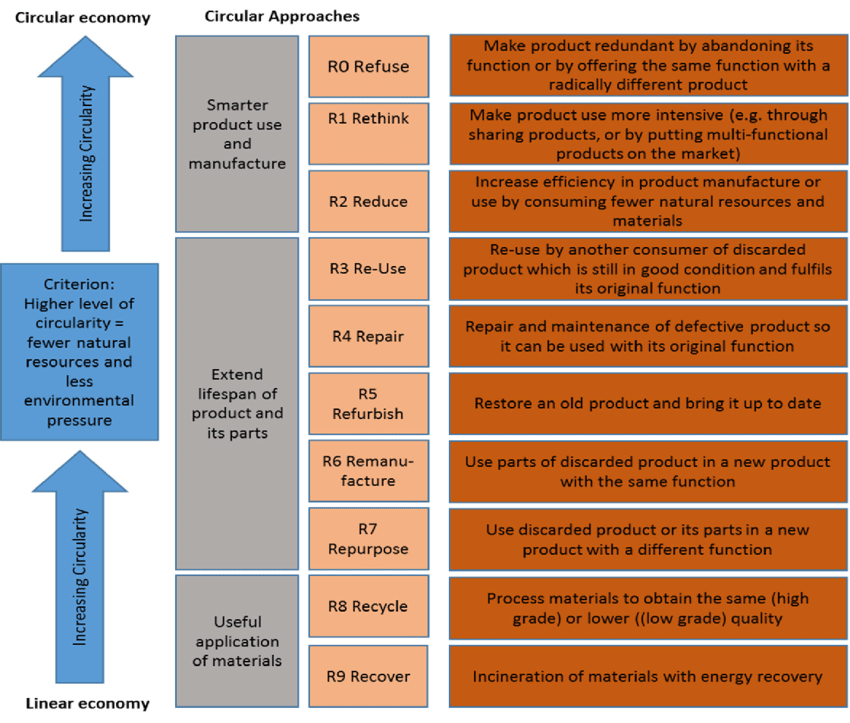

Recycling is sometimes used alongside and even in place of the circular economy, though only represents a small part of it. The circular economy requires a system-level consideration of resources. There is recycling, but there are eight other Rs, among them repurpose, reuse and repair.

Even if a company is not a recycler, they can participate in and help enable such an economy. For manufacturers, it is something they’re starting to take seriously. As with life cycle analysis in a previous era, tools are emerging to calculate a product’s broad impact. For example, Infrabuild recently became the first company in Australia to publish its Materials Circularity Indicator Score alongside Environmental Product Declarations. (See here for an explanation.)

The value

Last week Nine newspapers reported a PwC forecast of $1.86 trillion in potential new economic value realised over the next two decades here through the circular economy, across the building, transport, community and industry sectors.

Anna Minns, the co-founder and CEO of Boomerang Labs — the nation’s first CE accelerator — says her organisation has seen the most interest in tackling food waste so far after launching in 2019. A lot of innovative solutions had also been put forward in textile, plastic, consumer goods, agricultural waste and other areas, she has noticed.

“The sector is still in its infancy, but the opportunities are immense and endless for budding entrepreneurs,” Minns tells us.

Minns also believes recycling needs better infrastructure, as well as bigger input volumes, to develop, and the federal MMI is an important first step in this.

The 9R Framework of Circular Approaches with the production chain in order of priority. Source: Adapted from Potting et al., (2017, p. 5) [64].

(see https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-9R-Framework-of-Circular-Approaches-with-the-production-chain-in-order-of-priority_fig5_328662037)

“With the trialing of different collection models like the container deposit schemes and FOGO bins, and evaluating the return rate for different models and setting up community collection hubs, we can expand the items that are collected for recycling (input volume) and therefore the overall recycling rate.”

Plastics and circularity

As founder of Repeat Plastics (Replas) in 1992, Mark Yates has helped contribute a number of mixed plastic waste-to-product firsts. His CV lists design, test and installation of one of the first highway sound barriers used in Australia in 1999 and the first recycled plastic railway sleeper approved for use here in 2000 among these.

Since leaving Replas, Yates has founded o2 Plastics, which earned a Lexus X Mentored grant for promising startups late-last year.

He cites recent investment in PET-to-food-grade plastic recycling by major players — such as the $45 million Asahi/Pact/Cleanaway joint venture factory near Albury — as a potential game-changer, but this “still sits under avoid and re-use in the waste hierarchy, but a lot higher than waste to energy.”

When it comes to plastic recycling, this has had a “bumpy ride” over the years, observes Yates, and contains so many facets it is hard to speak about the whole industry with one statement. That said, he offers his thoughts on where the opportunities lie, which are worth quoting at length.

“The main opportunities in plastic recycling are bottle-to-bottle recycling but the barrier to this is the huge capital expenditure required to get started; at least now that we have container deposit legislation in most states one of the problems of a continuous, fairly clean supply of single polymer plastic has been alleviated.

“For all plastic recycling to work every part of the value chain must have an answer. Rigid plastics are relatively easy to recycle requiring less capital investment in processing equipment (other than food grade). But even the top processors of this material sourced from kerbside generate between 20 and 40 per cent waste in the form of fibres, residues, caps and labels so this waste stream is one opportunity.

“In the film area there are a few processors that process mainly post-industrial or specific post-commercial supplies like ag film that are set up to do large quantities but when you go down the scale into multi laminate mixed films like the material collected from supermarkets the only players in this area supply fairly niche markets at a premium price which isn’t conclusive to moving the huge amounts of this material that is still sent to landfill.

“Still to this day the focus is on the collection of material rather than what we are going to do with it, once it is collected. Single polymer to single polymer recycling must be at the top of the tree when it comes to plastics but I see huge opportunity in the by-products from this recycling process and of course mixed films, currently I am developing an answer for this material that will require the large supplies that are available and have huge end market opportunities but being only one person with limited funds this is taking much longer than expected.”

Austeng’s Ross and Lyn George, who featured in the first part of this series, are involved in a handful of startup companies with a sustainability bent as equity stakeholders and tech enablers. These include Viridi — a company producing nutrients and other value-add goods from wine waste — and Polymeric Powders, which is commercialising a world-first process to create engineered composite materials with unique properties from reclaimed tyre rubber and plastics.

A pipe made out of composite recycled tyre crumb/polyolefin plastic. (https://www.tyrestewardship.org.au/)

Lyn George says that despite the high potential of Polymeric Powders, attracting funding has not been easy — often the case here for manufacturing startups of any kind.

“You couldn’t get a better story in relation to recycling,” she tells us.

Beyond production

The circularity push will involve recycling, with manufacturers using and producing non-virgin material that gets kept in the loop.

“[Manufacturers] will also see change in the way we design and manufacture so that products are made to last a lot longer, and the materials can be cycled through the economy again and again, rather than used only once,” adds McLean.

According to one of the leading CE advocates, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation, currently most material is lost, and often after a single, short use.

The circular economy and the benefits mentioned above are not just for the manufacturers, though they would be transformative for them, from the way they use material to their business models and beyond.

“Importantly, the circular economy cuts right across the economy. We're not just talking about reducing food waste or recycling plastic consumer products, we're talking about everything we use – it might be locally capturing water, using rather than owning a washing machine, redesigning tech products to reduce e-waste, and using shared mobility instead of owning a car,” says McLean.

“…Really the core idea of the circular economy is around keeping materials in use for as long as possible in their most high-value form before recycling and reinvention into new products. That’s where reuse and repair come in, as well as sharing models, where ownership shifts to user-ship – like a subscription model clothing or white goods.”

The first part of this series, focussing on clean tech, can be seen here.

Picture: cleanaway.com.au

Subscribe to our free @AuManufacturing newsletter here.

Topics Analysis and Commentary

@aumanufacturing Sections

Analysis and Commentary Awards casino reviews Defence Gambling Manufacturing News Online Casino Podcast Technology Videos